Most people use the terms “study” and “learn” interchangeably. But they’re not synonymous. There are key differences between the two. And knowing the difference between how you learn or study a foreign language will help you reach fluency faster.

- Studying is a deliberate, conscious effort to get information into your brain.

- Learning is a subconscious, organic process. You can use your knowledge spontaneously. Another name for this is acquisitional learning.

Both have a role to play in your language learning efforts. But truly successful language learners tend to put more effort into learning and less effort into studying. If this sounds familiar to you, it’s because these ideas are not new. They’ve been around a while. In fact, Stephen Krashen developed them.

Study or Learn? Let an Expert Answer

Stephen Krashen, a highly regarded linguist, college professor, author, and lecturer, studied non-English and bilingual learning for more than 20 years. He recorded his findings in several books and close to 500 papers.

By the time I encountered Krashen’s work, I was pretty advanced in my own language learning journey. I’d formed about 90 percent of my teaching method, and Krashen’s theories helped reinforce the decisions I’d made about the optimal way to learn a language.

You Already Know One Language

Krashen is quick to point out that everybody has learned at least one language: their native tongue. The way toddlers learn to talk inspired Krashen and what motivates them to do so. Speaking understandably isn’t their objective. Their goal is to make sense of their environments, classify everyday objects, and understand the relationships among the people in their lives.

They absorbing language long before they say their first words. Talking is just a byproduct of making friends in daycare or wanting a cup of juice. Grammar lessons and rote recitation play no role in their language-acquisition process. Krashen insists that people of all ages can acquire foreign languages just that organically.

When first introduced, that theory contrasted to what had widely held as the gospel…

How Accurate Is Universal Grammar Theory?

Noam Chomsky is a pioneer of linguistic and cognitive sciences. In his Universal Grammar Theory, Chomsky proposed that children inherit a Language Acquisition Device (LAD) from birth. This means that people are born with grammar and linguistic structures already in their brains. This hardwiring is the basis of language learning. If continued grammar education does not strengthen the LAD, Chomsky believes this innate ability disappears.

Krashen disagrees. “We don’t master languages by hard study and memorization, or by producing it,” he wrote. “Rather, we acquire languages when we understand what people tell us and what we read when we get ‘comprehensible input.’ As we get comprehensible input through listening and reading, we acquire (or absorb) the grammar and vocabulary of the second language.”

For what it’s worth, my parents and grandparents were all fluent in the Circassian language. So were many of my elder, extended family relatives, and hundreds of thousands of ethnic Circassians. None of them were ever provided with formal grammar instruction. I know this for a fact because Circassian lacked a written alphabet until the 1930s. And even then, it was unknown to diaspora like my extended family members. As such, I tend to believe Krashen over Chomsky.

Five Theories for How We Learn a Language

Krashen’s Theory of Second Language Acquisition revolutionized foreign language instruction. Read the outlines of these theories to learn more about language learning.

The Acquisition-Learning Hypothesis

This distinguishes between traditional grammar-based learning in a classroom setting and acquisitional learning. The first is a conscious process. Conscious learning, Krashen believes, is never the source of spontaneous speaking. Students are merely learning the rules rather than absorbing the language in a meaningful way. They might master the grammar, achieve perfect syntax, and build impressive vocabularies, but proficiency isn’t necessarily comprehension.

Acquisitional learning is quite different. It’s a subconscious process that springs from the desire to understand others and be understood. It breaks down diverse social and cultural boundaries. It’s not only about proficiency, but it is also about knowing what is appropriate and respectful to say at any given time. It’s about the ability to grasp nuanced meanings and concepts like love.

“Language,” penned one unknown author, “is the mind’s opposable thumb.” Grasping things with an opposable thumb isn’t taught. It’s an organically acquired skill. Krashen would tell you to set aside the grammar books until you acquire the language. That’s when grammar makes more sense.

The Input Hypothesis

How do you acquire language? Krashen and Chomsky agree on this, at least: learning or acquiring any language requires comprehensible input. For Krashen, that means spending ample time listening and reading before you ever attempt to speak. It means saturating yourself in the targeted language, just as toddlers immerse themselves in language every day.

The comprehensible input, he feels, should always be one baby step ahead of your ability to understand it. He expresses this level of input as i+1. “I” represents your interlanguage, which is simply your skill level at any given time in the learning process. “1” signifies the next stage you aspire to. The i+1 formula prevents boredom and inspires you to soak up the language without getting frustrated.

It helps if the comprehensible input relates to your interests. Explore books and movies in your targeted language. Focus on art, history, religion, food, anime, or whatever medium appeals to you.

The Monitor Hypothesis

Unlike adults, toddlers don’t tend to go back and correct themselves when they violate grammar rules. Foreign language students are masters of self-analysis, self-editing, and second-guessing, especially if they’re perfectionists, to begin with.

Krashen advises you to stop overthinking things. Instead, focus on what you hope to communicate and spit it out. Learning from your mistakes is as valuable in the acquisition process as being right.

The Natural Order Hypothesis

In any language, vocabulary and grammar skills are acquired in a certain order, no matter who learns them. This order may not necessarily jibe with the course syllabus.

Some elements of grammar, like possessives and third-person plurals, are known as late-acquired skills. You may breeze along on early-acquired elements and hit a wall when you can’t grasp late-acquired ones. That’s understandably frustrating, but learning a language is a natural, brain-ordered process that goes at its own pace. There’s no rushing the brain.

The Affective Filter Hypothesis

Charles Van Riper had a severe stutter, and his youth was a long series of humiliations. He once pretended to be deaf and mute just to get a job as a hired hand on a farm.

One day, an old man with a severe stutter came to chat with the farmer. Van Riper overheard him and worked up the courage to approach him on his way out. They had a meaningful talk, and the old-timer told Van Riper to relax. “I’m too old and tired to fight myself now,” said the visitor, “so I just let the words leak out.” Van Riper never forgot that.

Van Riper opened a speech clinic in 1936 and became a renowned pioneer of speech therapy. People still use his methods widely today. The crux of Van Riper’s approach is to reduce language learning anxiety that only makes speaking worse. The goal is not to stop stuttering, but to communicate well despite the stutter. The goal is to stutter fluently.

Learn or Study Stress Free

Krashen’s Affective Filter Hypothesis uses the same approach. No one can learn to speak a foreign language in a negative, stressful environment. The pressure to get everything right tends to be self-imposed. It’s marked by fear, anxiety, embarrassment, or being overly concerned with impressing others. If you feel that way, you have your affective filter up.

The affective filter interferes with comprehensible input, and the entire learning process becomes counterproductive. Krashen encourages you to relax, take a deep breath, and stop worrying so much about your listeners. As Van Riper would put it, stutter fluently. It’s infinitely more satisfying.

It’s Natural to Learn, Not Study

As Krashen points out, every human being has learned at least one language. At the same time, a large number of people on the planet speak more than one. While it may be very common to speak only English in the United States, there are large swaths of Africa, Asia, and even Europe where it’s the norm to find people fluent in multiple languages.

That’s because language learning is a natural process. My parents learned to speak Circassian without ever opening a book or stepping into a classroom. They are functionally illiterate in their ethnic language. Yet, they speak it with an eloquence and ease that I dream of one day achieving. My parents, like many others, learned their languages naturally.

Natural language learning is how everyone learns to speak their first language. It’s how people who grow up in a bilingual household learn their first two languages. You listen to how the people around you speak. Your brain notices the context, tone, grammar, and flow of the speech. This observation is how the brain learns language as efficiently and effectively as possible.

However, learning a second language in a classroom does not come so easily or naturally. This is because most classroom learning focuses on a complicated set of grammar rules, memory drills, and verb conjugation tests.

Study Isn’t a Natural Way to Learn a Language.

Trying to learn a second or third language in this way is difficult, frustrating, and loathsome. Fortunately, natural language learning is a way to learn another language without getting annoyed or bored with the process. This is where I ask you to join me in being a little lazy. I’m asking you to spend less time studying your language and more time learning (or as Krashen would say, “acquiring”) it.

Balance How You Learn or Study

I’ve come down strongly in favor of learning in this section. We can’t just decide between study or learn. Both are necessary. I believe learning is more effective and more fun. And I hope you’ll choose to focus your time there.

How much time?

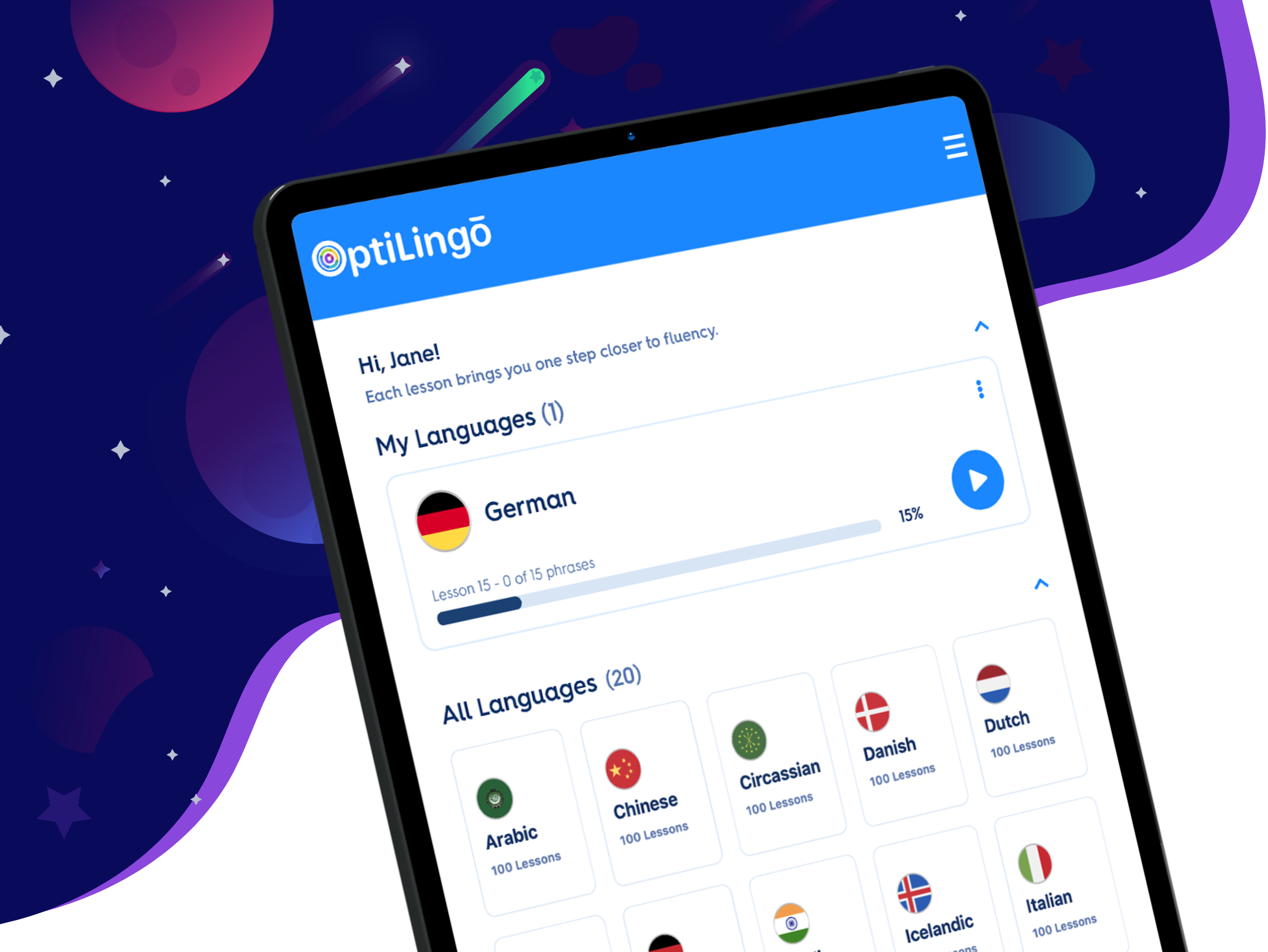

In my own language learning, I take an 80/20 approach. I aim to use about 80 percent of my language-acquisition time toward learning (listening to audiobooks, conversing with native speakers, watching movies, etc.) and 20 percent of it studying (using books, classes, apps, etc.) – but each person will find the right balance for him- or herself.