How to Retain What You’ve Learned

Language learning is work. Hard work. And to make sure you’re not wasting your time, you need to know your efforts are going to take you somewhere. But how can we learn the most efficiently? To figure that out, you need to answer 2 questions. How can we best retain what we’ve learned? And, how quickly can we integrate new material? With the right answers, you’ll easily remember your language lessons.

Learning how your brain works to store information is the best route to optimizing your time. To make your learning most efficient, we’ll look at effective study methods, the role of sleep, the reason we forget things, and ways to improve our recall.

Cramming Language Lessons Doesn’t Work

Think back to your school days…

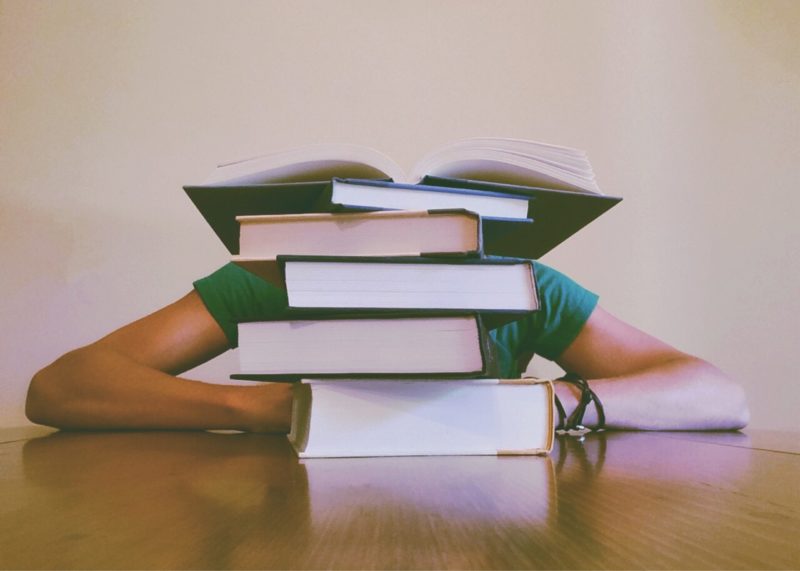

Remember studying for an exam? After weeks of assuring yourself that you have plenty of time, the all-important final exam looms tomorrow. You had planned to start early. You sketched out a study calendar weeks ago. Where is it now? You curse yourself for your shameless procrastination. Your only alternative is to turn off your phone, order a pizza, brew a pot of coffee, pull an all-nighter, and hope for the best.

Unfortunately, science proves that cramming doesn’t work. The best way to master new material is to take it in small, digestible bites over a few weeks or months. Each time you return, your brain recognizes the material and snaps to attention. It reinforces the knowledge so you can remember it.

In a study at the University of California, results showed that for 90% of participating students, learning over a period of time was more helpful than cramming. However, more than 70% of the students insisted that cramming had been more effective. How were they tricked into believing that? People are creatures of habit. The more familiar a study method is, the more likely you are to believe it works.

Cramming doesn’t work when studying for an exam. And it doesn’t work for remembering language lessons, either. Regular study sessions are the key.

Language Familiarity vs. Mastery

If you’ve always made flashcards or highlighted pertinent material or learned by rote, you convinced yourself that you can’t learn any other way. None of those methods are necessarily bad. But, just because they’re familiar doesn’t mean you’re really learning or retaining new information.

Here’s an example:

After a long cramming session, you might listen to some recordings, take notes, or make flashcards. This study approach may feel like a well-worn security blanket. (It’s what you grew up with in high school or college). You might even retain a number of phrases or sentences with this approach.

In the short term, you could start to feel confident, or even a bit smug. You can’t wait to show off your newfound fluency to a friend or a loved one. But when it comes time to demonstrate your mastery, you choke. Maybe the word or phrase is on the tip of your tongue. But, it just won’t come out. Or, maybe it’s buried deep in your mind, and you can’t even recall it. Maybe an entirely different word or phrase keeps popping into your mind…

Just because you’re familiar with the information doesn’t mean you’ve mastered it.

The highlighted texts and flashcards become familiar because they’re processed through sensory areas, such as the visual cortex. Your brain supports comprehension and recall in entirely different areas. The frontal cortex and temporal lobe, for example, create memories as knowledge is revisited and built upon. Memory is a coordinated effort that takes place all over the brain.

The Role of Sleep with Memory

One common misconception is that actively thinking about learning something – putting our minds to it, so to speak – will help us recall it. Being alert is commendable, but scientists know that reorganizing new information and providing structure and context for it is more beneficial when it comes to retention.

You can and should lay out your new language in a way that makes sense to you. Afterward, let your brain do the work for you. Surprisingly, one of the most important brain functions takes place while you’re sleeping.

Every random bit of knowledge you pick up during the day gets categorized and sorted in order of priority during rest. Everything you’re learning is filed away in a nice tidy cabinet organized by date and importance. During sleep, your brain keeps you from obsessing over the nouns, verbs, and tenses you already know, and instead helps that complex new piece of information you learned take firm root.

Whatever you do, get plenty of sleep. Sleep is crucial to overall good health. It wards off a number of serious diseases. It makes exercise more beneficial. It keeps off excess weight and helps us to manage stress. Those advantages are well worth getting quality rest for, but sleep’s greatest benefits pertain to learning.

For far too long, our society has treated sustained sleep as a form of laziness that serious students and business people should avoid. The smartest guys in the room don’t linger in bed when they could be at their desks closing big deals at 6 a.m., right?

Nothing could be farther from the truth. Trying to learn anything new without getting adequate sleep is an exercise in futility. Sleep is strongly linked to learning, comprehension, and retaining new knowledge.

Here are the accounts of three revealing experiments.

1. Sleep Consolidates and Relocates Existing Memories

Researchers at the University of California studied the role of sleep spindles in cognitive performance. Sleep spindles are sudden bursts of brain activity in the second stage of light sleep. The experiment began at noon. 44 students had been recruited to memorize 100 names and faces. When their study time finished, the researchers immediately tested the students.

Half the participants then took a 90-minute nap. Scientists measured their brain activity while they slept. The other participants stayed awake. Six hours later, both groups were assigned 100 new names and faces to memorize. All were tested on their recall.

The students who stayed awake all day performed significantly worse on their 6 p.m. test than on their 12 p.m. test. The students who napped, on the other hand, did approximately 10% better on their second test.

Clearly, our ability to learn is compromised as the day wears on, and sleep provides a much-needed memory boost. That’s because sleep spindles transfer new, relevant memories from deep in the hippocampus to the prefrontal cortex. That frees up space for all the new information that will pour in tomorrow. It’s a little like organizing a storage unit to fit many more items inside.

The more you sleep, the more sleep spindles you have. The more sleep spindles you have, the more you learn and remember.

2. Sleep Increases Motor Skills

Each student received a sequence of five single-digit numbers to repeatedly type in order on a computer keyboard. It sounds simple enough, but the results were less than impressive. After a good night’s sleep, the participants were retested. The average improvement in the morning test was 20% in speed and a whopping 39% inaccuracy.

This point is important because speaking a language requires your brain to develop new motor skills associated with quickly and easily pronouncing new words and phrases.

3. Sleep makes you less forgetful

John G. Jenkins and Karl M. Dallenbach, two pioneers in the study of sleep and memory, performed a groundbreaking experiment in 1924.

Test participants were taught nonsense syllables. Every hour, they were asked to remember as many of the gibberish syllables as they could. Half the participants stayed awake all day for the study. The other half slept. And someone woke them up every hour to test their recall.

As the day went on, the participants who stayed awake gradually forgot their syllables. The students who slept were somewhat forgetful in the first few tests, but their memories eventually stabilized until they could perfectly recite their syllables.

The experiment proved that sleep helps keep newly learned information intact.

When it comes to remembering your language lessons, it’s tempting to cram all you can into long, focused sessions. However, science proves you’re better off hitting the sack and letting your brain do the heavy lifting.

Remember Language Lessons By Fighting the Forgetting Curve

Now you know how important sleep is to learning. But what about that evil enemy of learning called forgetting? You’ve probably been there. You had it down perfectly just a week ago. After two hours of focused study, the Italian or Swedish or Japanese rolled fluently off your tongue…

Had you immediately landed on foreign soil, you could have bantered with the natives as though you’d known them all your life.

What happened?

It hardly seems fair, but almost nothing roots firmly in your brain the first time you learn it. It’s a real and rather depressing fact of life. If knowledge is not reinforced, it’s lost over time. On the bright side, life would be awfully dull without learning challenges. No one would get very excited about new inventions, breakthrough medicines, or space exploration.

Fortunately, your sense of accomplishment when you permanently remember your language lessons will be well worth your efforts. All you have to do is fight the Forgetting Curve.

Discovering the Nature of Memory Loss

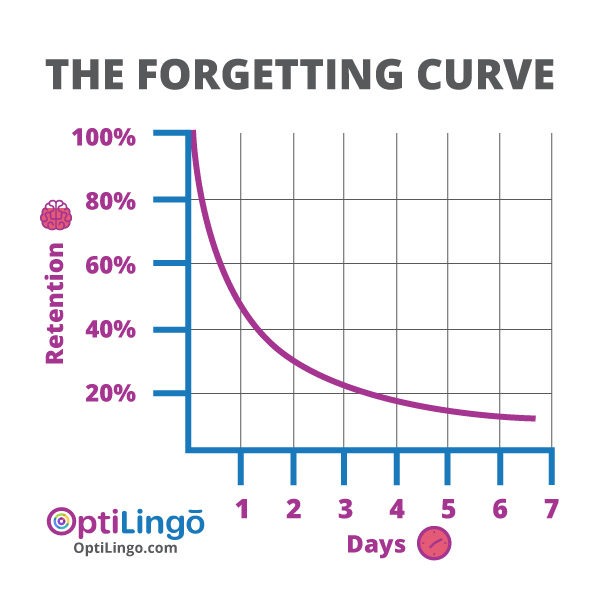

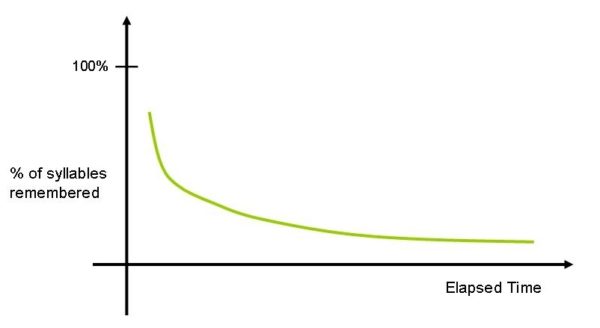

Hermann Ebbinghaus was a 19th-century German psychologist and a pioneer in the experimental study of memory. He must have been a real glutton for punishment. Basing his research on spaced learning, he tested his own memory over various periods of time and plotted the data. His resulting graph looks like the architectural drawing for a steep slide at a water park.

Just one day after learning something new, your memory of it is only slightly better than 50%. The downward slope is less dramatic after the first couple of days, but by the seventh day, retention is less than 20%. Ebbinghaus dubbed this the Forgetting Curve. It is a reliable prediction of the rate of memory loss over time. Once he’d gathered all the data from his spaced learning studies, he plotted it on a graph that looked something like the image below.

Now, it bears pointing out that Ebbinghaus didn’t invent this graph. Rather, it is an illustration of the point that his research proved. Information you study fades over time based on two things. The strength of the memory and the passage of time.

The Strength of the Memory in Language Learning

Strong memories are easier to recall than weaker ones. That said, memory is subjective. Who can measure the strength of a memory? However, knowing that whatever we can do to make our learning experience stronger (use media, involve what we enjoy, make learning relational, move facts from our passive memory to active memory, etc.) helps us retain the information more easily.

What Happened Since Your Last Language Lesson?

Research done subsequently to Ebbinghaus has shown that learners forget an average of 90% of what they learn within the first month of learning it. While this statistic may vary for one piece of information versus another, think of it as an average. If you were to memorize 100 foreign language vocabulary words and then ignore them, a month later, you’d only remember 10 of those words.

How to Remember Your Language Lessons

Now that we know how memory works, we can do something about it! Here are a few ways you can leverage spaced repetition to improve recall.

The Power of Spaced Repetition Systems

Virtually everything you’ve read in this section has been a lesson in the value of Spaced Repetition Systems, or SRS. A Spaced Repetition System is any technique that incorporates increasing intervals of time between subsequent reviews of previously learned materials. Physical flashcards are among the earliest forms of SRS, and today, SRS is built into a lot of modern language-learning software.

For the past decade, I’ve worked as an endangered language activist, laboring to preserve and promote my ethnic language, Circassian. I know I’m not the only person interested in this topic, but I’d argue I’m probably the most motivated guy in the field for one simple reason: if I fail, my language will die, and my cultural heritage will fade from existence.

Over those 10 years, I’ve figured out how to dramatically reduce the amount of time it takes to learn and remember your language lessons. In fact, I’ve cut it in half. Not surprisingly, the key is SRS.

Here’s a quick summary of how SRS works. On the very first run-through of new content, you’re learning, you go through and mark any items you don’t recall. Each time a new memory begins to fade, you re-energize it by refreshing and strengthening your memory.

Every time after that, though, the SRS system works its magic. In the second review session, the system only asks you to remember the stuff you forgot last time.

As noted in the earlier example, without revisiting your study notes, on average you’d forget 90 of those 100 words you memorized. But that’s just an average. Each word has its own unique forgetting curve, and some are longer than others.

Intelligent Scheduling

SRS is clever. It doesn’t merely keep track of what you forget and what you remember; it also predicts when you’re most likely to forget things, based on an algorithm that gathers information about you as you study. It can then intelligently schedule items to be reviewed at the most efficient time possible: just before you forget them.

So each time you use SRS, it reveals what you really should be studying at that point in time. This frees you to focus entirely on studying. The system handles all the scheduling and arranging for you.

Flashcards: The Original, Old-School SRS

Early SRS systems were implemented with real, physical flashcards. This was a huge step up from rote learning, but couldn’t quite take advantage of the full implications of SRS.

Now, with SRS software, the computer not only handles all the calculations, but it also does so in incredible detail, considering a wide array of information to optimize your study time. That means you achieve more in the same amount of time.

In other words, you spend less time and don’t fall behind in your studies.

The applications of this for remembering your language lessons are obvious. Place the content you’re learning into the SRS, put some time in each day, and let the software handle the rest.

Obstacles to Remembering Language Lessons with SRS

Although SRS can be very powerful, it’s not a language learning method—just a tool you should incorporate into your broader efforts. Many learners overestimate what SRS can do when they first find out about it. I was a classic example of this. It’s easy to get into the mindset that all you have to do is mindlessly add things to the system and you’ll magically learn it.

Ultimately, you still have to put the hours to acquire your new language – SRS just makes it more efficient. But it’s tempting to add too many vocabulary words too quickly, making your reviews tedious and time-consuming. Try to keep the content in your SRS trimmed to a minimum unless you really want to put in hours every day.

Also, remember that your brain is extremely good at learning in context. A lot of people find that even though you can easily remember an item when reviewing it in the SRS system when it comes to actually use it in real life, it’s not as easy. This is why no matter how good your review system is, you still need to get out there and really use the language. Ultimately, SRS is a very powerful and effective tool – but it is not a comprehensive learning system.

How Quickly Can You Learn a New Language?

Now that we’ve looked at how best to retain what we’ve learned, let’s turn to another question most people trying to remember their language lessons ask: how fast should I expect to progress?

It takes time to encode new content from short-term to long-term memory. It also takes time to transfer passive memory into active memory. Once knowledge is active, you can use it with ease. But getting there is a time-consuming process that involves repetition. You cannot escape repetition. Your brain needs repetition to encode new memories. The only way to learn faster is to maximize your cycles of repetition, and even that has limits.

How Many Repetitions Do You Need?

In 1967, Dr. Paul Pimsleur published a popular article illustrating that it takes an average of seven repetitions to process information into long-term memory. While Pimsleur fails to point out his methodology or data, he notes that he used intervals ranging from five seconds to two years to come to these results. Still, he never states why he chose those intervals.

Based on my experiences and incorporating the algorithms of prominent Spaced Repetition Systems in use today, I would argue that 10 to 20 repetitions is more ideal. Going below 10 repetitions loses the benefits of encoding information into the active recall. As a result, your efforts won’t yield the highest results.

The problem with establishing a minimum is that it creates the wrong mindset. Some words and phrases take longer or shorter to encode than others. Finishing 7, 15, or 80 repetitions does not guarantee victory. Encoding information is a constant process as memories fade over time. Exposing our brains to critical information is part of the retention process.

How Fast Can You Remember Language Lessons?

If you were to aim for an average, you could reasonably say that 15 repetitions over six to eight months would result in mastering new information.

To use an example, let’s assume you want to learn 1,500 phrases in your target language.

As a result, you study 15 new phrases each day, every day, without missing a beat. After 100 days, you would reach the last of your 1,500 phrases. But on that last day, you’d still need another six to eight months for the repetitions of those last phrases. And because 100 days is a little over three months, you’d need between nine and 11 months to master all of your target information.

Even if you went faster and really strained your brain, learning 50 phrases a day, you’d still need seven to nine months – and you’d sacrifice mastery in the process.

The Visual-Spatial Loophole

There is one loophole you can use to learn faster. People struggle to learn words presented abstractly. Imagine if you had to memorize this list of words:

- apple

- beautiful

- book

- bright

- carried

- down

- grandmother

- green

- her

- mountain

- old

- pie

- red

- waiting

- warm

- was

- where

- with

- woman

How successful do you think you would be? How long would it take you? Chances are, if you needed to study these words, you would eventually string them together to provide some context.

As a result, you might come up with a sentence like this: “The beautiful woman carried a bright red book down the green mountain, where her old grandmother waited with a warm apple pie.” Studying that sentence and visualizing the story would yield far greater results than trying to remember each word individually.

We do this all the time. When we enter a new situation, our brains quickly map out the area to become familiar with it. This is because we’ve evolved to encode visual-spatial memory as part of a survival mechanism.

Serial polyglots exploit this loophole to remember your language lessons faster. Once they have a firm foundation, they move past basic vocabulary and into consuming books, movies, music, and other mediums that provide context for the brain to retain greater volumes of information faster. You need to have at least a basic understanding of your target language before moving into these complex systems, however.

Leverage Limitations to Remember Language Lessons

While there are physical limits to how fast we can learn and how well we retain that material, understanding how memory works help to motivate and inspire us to get the most out of our effort.

As a language learner, you should approach forgetting with a different frame of mind. Instead of growing frustrated, remember the process. Imagine your brain forming synapses with each new lesson you undertake. This will help you remember your language lessons in the long run.

As you push forward and continue to study, you gain momentum, knowing that each repetition gives your brain another opportunity to undergo the physical changes it needs to provide you with rapid access to new memories. You can relax in the knowledge that you’re using the best techniques to retain what you learn.