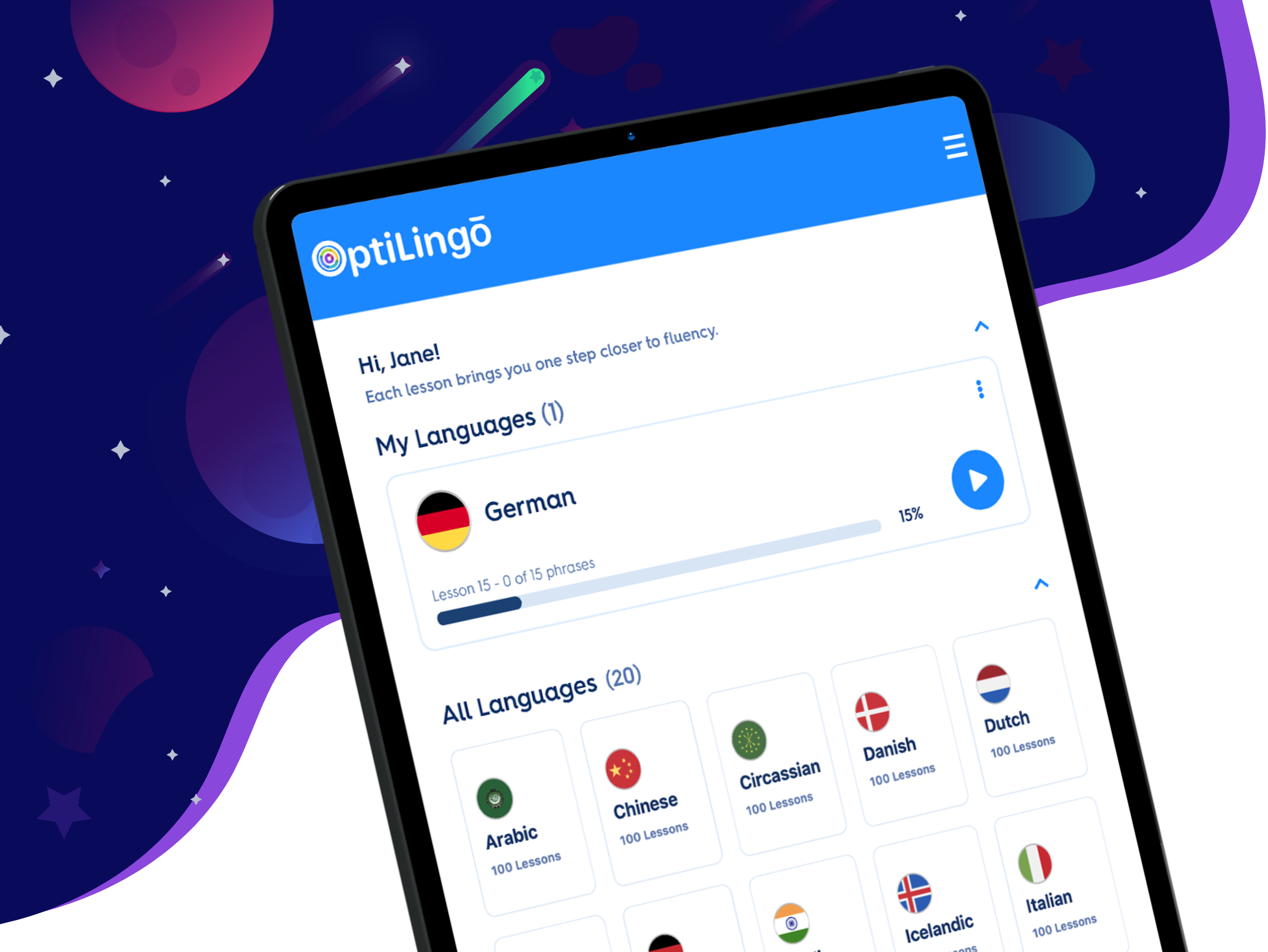

Language learning is the long-term process of building confidence, competence, and fluency in a new language. In turn, it relies on incorporating knowledge, experiences, and abilities and storing them in your memory so you can use them to communicate in the language you are learning.

While learning our first language is very natural, when it comes to learning a second (or third or fourth) language, you still must learn how to learn.

Many people have mistaken ideas about how learning works. In turn, this has implications for how they view learning a new language, and this causes them to employ useless study techniques like rereading and repeatedly practicing the same thing.

As a result, our educational system is saturated with inefficient methods and learning myths, which educators, coaches, parents, and peers spread.

In contrast, the best learning techniques are frequently the opposite of what you might expect. In this post, you’ll discover how to learn a new language. We’ll cover how the learning process works and how to use study methods backed by scientific evidence regarding how your brain processes and remembers knowledge.

Learning a New Language Is Composed of Two Key Steps:

- Comprehension: To comprehend a fundamental concept (vocabulary, verb conjugation, grammar), you must understand the context in which it occurs.

- Retention: You must retain the knowledge to refer to it when necessary and build on it with a more in-depth understanding. This is sometimes referred to as active recall, the cornerstone of language fluency.

Understand Your Target Language’s Structure

When you begin learning a new language, you must first identify the rules, which are the underlying concepts that will direct you when you apply this knowledge to communicate in real-life situations.

In that case, you’ll obtain a more meaningful grasp of the language than if you had just memorized the facts from your textbook or lecture notes. Also, you must be able to sift out irrelevant material to draw out the essential themes.

Here Are 2 Methods for Determining the Rules of Your Target Language:

- Analyze several examples simultaneously as opposed to one at a time to more clearly identify the common thread. Draw out the underlying ideas of the linguistic concept you’re studying.

- Compare and contrast two different problems to see if any patterns will help you understand the rules of the language and solve each challenge that arises.

Once you’ve grasped the ideas, combine them with pertinent past information. Structure building involves creating context. This improves your understanding of the language.

You can develop mental models using structures that combine related ideas or abilities into a flexible skill set. This allows you to communicate fluently in your target language in various situations.

For example, consider driving a car. It involves motor abilities to apply the appropriate amount of force while turning the wheel and knowledge of traffic laws.

Initially, it may seem like you’re juggling multiple skills at once. Still, with practice, all these abilities are combined into one mental model that allows you to drive without consciously considering each separate move.

In the same way, you can turn the individual linguistic skills related to your language (such as vocabulary, conjugations, and listening comprehension) into a mental model that will make every conversation feel more fluid.

Mastery requires mental models, such as the driver responding instantly when another vehicle unexpectedly cuts into their lane or brakes directly in front of them. As a result, you can navigate any circumstance with more mental models. Additionally, applying your mental models in varied scenarios helps you become more adept at doing so.

For example, you will be more able to use your driving abilities to operate a bus or an RV if you have experience operating a vehicle in various road, weather, and environmental situations.

Practice Retrieval and Boost Retention In Your Target Language (3 Rules)

Knowing a language is one thing, but using it when the occasion arises is what counts. The more quickly you can recall information when needed, the better your memory. Rereading is a common strategy for committing information to memory. However, this method only stores the data in short-term memory, making it ultimately ineffective.

Instead, retrieval practice—any activity that asks you to recall what you’ve learned—is the most efficient technique to increase new information retention.

For example, you can practice retrieval with flashcards, self-tests, quizzes, and reflection. By evaluating your approach to a particular aspect of your target language and how you may improve the next time, you increase your chances of retention.

To optimize the advantages of your retrieval exercise, adhere to the following three rules.

1) More challenging retrieval results in higher retention.

The more demanding a piece of information is to retrieve, the more firmly your brain stores that information in your memory.

This desirable complexity can be produced, for example, by employing generative learning, which necessitates that you recall the solution (for example, using flashcards or short-answer questions instead of multiple-choice questions).

Another strategy is to postpone your retrieval exercise so long that your memory has become somewhat hazy, and your brain is forced to work harder to recall the data.

2) Repeated testing enhances memory.

Regular testing strengthens understanding, improving your capacity to apply the language in various situations. Additionally, your retention will be more durable the longer you take standardized tests, even after you believe you have mastered the language.

The best testing plan involves adding a slight delay before the initial test, followed by frequent testing at varied intervals.

3) Corrective feedback is essential.

Corrective feedback is essential to ensuring students retain the proper knowledge and preventing them from recalling incorrect responses.

Immediate feedback might act as a crutch for learning and mastering the language, so corrective feedback works best when given after a brief interval.

Instant feedback is similar to learning to ride a bike while using training wheels; the correction is so automatic that you start to rely on it, which prevents you from actually learning and mastering the skill.

Space Your Training in Your Target Language

As we mentioned, spreading out your retrieval practice produces pleasurable challenges that enhance your recollection.

Spaced repetition practice provides your brain with the time it needs to reinforce new knowledge. Learned information is stored in your long-term memory (a process called consolidation) as opposed to focusing on one skill or topic at a time (massed practice).

The following two methods will help you automatically space out your practice for the best results.

1) Interleaved practice involves practicing a variety of related concepts or abilities.

Instead of categorizing your language studies by topic, try mixing up the questions and working on various topics in one sitting.

Start with some vocabulary flashcards, then conjugation practice, then some listening exercises, and so on. Interleaving gives you time for practice and facilitates your ability to integrate the various topics you mix in.

The secret of interleaving is to move on to the next idea or skill before you’ve finished honing the previous one. Although changing gears before you’re ready can be annoying, doing so will increase your long-term retention.

2) Using talent in many situations is known as varied practice.

This tactic improves your comprehension of the underlying concepts and your capacity to use the language in various contexts, such as honing your speaking skills by practicing in different situations.

How Self-Evaluation Can Hinder Learning a New Language

As you progress in your language learning, you must be aware of what you already know, what you don’t know, and what you still need to study to broaden your knowledge. However, learning might be hampered, as people frequently misjudge their knowledge and skills.

Humans Find It Difficult to Assess Their Abilities Appropriately for Several Reasons:

- Perceptual illusions: Illusions cause your perception to be distorted, causing you to misinterpret noises, images, or other feelings. Pilots, for instance, may experience optical illusions or, in rare cases, illusions that lead them to believe objects are level when they are inclined.

- Cognitive Biases: Systematic flaws in your thinking that affect your judgment and decision-making are the root causes of cognitive biases. The bandwagon effect, for instance, is a cognitive bias that increases people’s propensity to think or act accordingly with what others are thinking or doing.

- “Hunger for Narrative”: People tend to misread situations because of the innate drive to construct stories that explain why things are the way they are. Even though narratives have a more significant impact than objective facts, most people are unaware of or underestimate this impact. For instance, if your parents made a lot of money by running their own business, you might believe strongly in the idea of climbing the socioeconomic ladder independently and find it difficult to see the case for social welfare programs.

- Distorted Memories: People with distorted memories may embellish them with exaggerated details or even assert that they recall events that never occurred. Human memory is naturally malleable, which makes it susceptible to errors and false recollections. For instance, if a witness to a crime views a suspect’s images before looking at a lineup, she is more likely to make a false accusation against someone in the lineup if she has already seen his photo.

- Mistaken Diagnosis: It is also possible to make a mistaken diagnosis and fail to realize that a different strategy is necessary than your mental model suggests. For instance, brain surgeons must generally operate carefully and steadily. Still, if certain circumstances cause pressure in the brain, they must act rapidly to save the lives of their patients.

- Overestimating Skills: People who are ignorantly incompetent tend to overestimate their skills and undervalue their need for development.

You cannot identify your knowledge gaps when these variables make it difficult to evaluate your skills and knowledge. For example, when a real-life scenario requires that you fluently speak the language you’re learning, you’re less inclined to spend extra time practicing the skills that need improvement.

You may, however, sharpen your sense of language fluency.

Use These Learning Techniques to Maintain a Clear Perspective:

- Apprenticeship: Comparing your language skill level to that of a native speaker or expert offers you a better understanding of where you stand in comparison.

- Peer Instruction: Working with your peers to learn a language helps you avoid the kinds of misunderstandings that can arise from independent study.

- Peer Review: Working with other students or professionals can determine if you’re doing well. You may make the necessary adjustments and improvements if they provide honest criticism.

- Team Learning: Working in a group with complementary skills, everyone can learn from one another. Each person’s strengths are also on display, and it’s usually evident if somebody is lacking. For example, perhaps you have a strong Korean vocabulary but struggle with pronunciation; by studying in a group, you can lend your skills to those with a lesser vocabulary and accept help from those with better pronunciation.

- Real-World Simulations: The best method to develop your abilities and identify gaps between conceptual learning and application is to train in scenarios similar to those you would encounter in real-life situations. Regarding language learning, this might mean visiting a country where your target language is spoken or exchanging letters in that language with a pen pal.

Don’t Let Your Learning Preferences Limit You

In addition to illusions that distort your view of your knowledge, myths regarding your learning capacity might obstruct your language learning. For example, it’s a widely held concept that everyone has a preferred learning style, such as auditory, kinesthetic, or visual, and that this style of instruction should be matched for optimum learning results.

This Belief Suffers from Two Issues:

- Although different people prefer to learn differently, research indicates that learning is not hampered when the teaching method does not correspond to the preferred learning method. All students learn most effectively when the method of education is appropriate for the subject being taught, such as using visual aids to teach geometry, audio to teach a foreign language, or kinesthetics to teach motion-related concepts in physics.

- A student’s perception of her skills and potential tends to be constrained when learning styles are the main focus. This constraint may impact the student’s willingness to attempt new things, her level of effort, and her ability to persevere when facing challenges.

The Problem with Intelligence in Language Learning

The illusion that intelligence is fixed and the fallacy of learning styles also prevent people from learning a new language. People don’t put as much effort into learning when they think they were born with a specific capacity for it. Intelligence isn’t a permanent quality.

The average I.Q. of Americans has increased over time. Several variables, such as a person’s genes, environment, socioeconomic level, and diet, impact I.Q. scores.

Utilize Your Intelligence to the Fullest

To optimize your intelligence, you don’t need to enhance your I.Q. The following methods will help improve your skills:

- Develop a growth mindset. People with growth mindsets put in more effort, take more chances, and see mistakes as teaching moments because they know that effort and discipline are essential for learning. In contrast, those with fixed mindsets think intelligence is unchangeable, and that success is determined by it. As a result, they feel helpless in the face of failure because they believe their lack of intrinsic talent is to blame.

- Engage in intentional practice. To become a master, deliberate practice is essential. Because it takes place alone, it differs from simple repetition. It’s goal-oriented and continually challenges you to surpass your potential. It takes effort, failure, problem-solving, and repetition to develop mental models and master a new language.

- Employ memory cues. Utilizing comfortable triggers and memory cues assists in organizing and retaining information. For example, memory aids can be as simple as acronyms or as sophisticated as memory castles. Many language students find memory cues extremely helpful when memorizing vocabulary or grammar rules.

Implement These Evidenced-Based Techniques

Here are some suggestions for practicing these concepts now that you know them.

Learners and students: Actively engage in your learning.

- Take periodic breaks to ask yourself questions about the main ideas in the knowledge you are gaining about your target language.

- Create a metaphor or mental picture that illustrates the new language principle you are learning.

- Attempt to define a concept before locating a definition; try to resolve issues before understanding the solution.

- Write down questions while you study so you may test yourself afterward.

- Test your knowledge of new and old material regularly, mixing up different topics (vocabulary, conjugation, listening comprehension, forming sentences, etc.). Review the subjects covered by the questions you get wrong.

Instructors: Teach your pupils the fundamentals of effective language learning, including the value of failure, pushing themselves outside their comfort zones, and the principles of desirable difficulties. Use the principles of spacing, interleaving, and diversity in your lesson planning to incorporate them into your curriculum.

- Conduct regular, low-stakes tests that include previous material.

- Offer study tools like practice exams and short-answer exercises that use retrieval practice, elaboration, and creation.

- Tell pupils to spend ten minutes at the end of class summarizing everything they learned that day. They should recheck their notes after ten minutes to see what they might have forgotten and then review the material.

- Divide students into small groups to collaborate on complex conceptual issues the teacher raised or on ideas they find challenging in the course content.

Learning a New Language Takes Time

Language learning is the long-term process of building confidence, competence, and fluency in a new language, which relies on incorporating knowledge, experiences, and abilities and storing them in your memory so you can use them to communicate in the language you are learning.

While learning our first language is very natural, when it comes to learning a second (or third or fourth) language, you still must learn how to learn.

Most individuals have incorrect notions about learning, causing students and teachers to impart knowledge ineffectively.

These Ineffective Techniques Include:

- Rereading a text multiple times

- Drilling the same skill repeatedly

- Presenting information in an easily digestible way

- Designing lessons that match students’ learning styles

Contrary to popular belief, these “best approaches” for a thorough understanding and long-term memory are illogical. This guide helps you avoid these pitfalls by instructing you on learning and studying a foreign language using scientific evidence regarding how your brain processes and remembers knowledge.

We’ll look at more ideas and methods for learning more efficiently in later posts.

The Following Are Some of the Guiding Principles:

- Hard learning stays with you.

- The learning process must include making mistakes and learning from them.

- You are not a good judge of how well you understand a course or recall information you have already learned.

- Learning is not improved when the class accommodates students’ preferred learning modes.

- There is no predetermined level of intelligence.

The Techniques You’ll Discover Include:

- Forming Mental Models: Compiling related ideas or abilities into a single, fluid skill set.

- Retrieval Training: Memorizing information.

- Generative Learning: Figuring out a problem before answering it, even if you get it incorrect.

- Spacing Your Practice: Separating your practice and study hours.

- Interleaving: Spreading out your research across a variety of related disciplines.

- Diverse Practice: Using a skill in many situations.

By applying these concepts to your language studies, you’ll learn more effectively and be more likely to gain mastery in your target language.