What Happens in Your Brain While You Learn?

Before getting into the methods for improving your language learning, let’s discuss what happens in your brain during the learning process.

1) Encoding

Your brain records new information as memory traces—mental representations of knowledge. As if your brain were making notes in a notepad, memory traces are kept as short-term memory.

2) Consolidation

Because the memory traces in your short-term memory are still somewhat malleable, consolidation fortifies the information and sends it from your short-term memory to your long-term memory.

According to scientists, consolidation is the process through which your brain reviews the lesson, fills in any gaps in the memory traces, and makes connections between new material and previous learning and experiences. Experts believe sleep helps with consolidation, which can take hours or even days.

For example, consolidation and essay revision are comparable experiences. Although your initial draft is imperfect, it captures the main concepts, such as the encoding procedure. The paper grows more polished as you modify it and fill in the blanks.

After setting it aside, when you return to write the final draft, your ideas become more organized. You get a clearer understanding of your thesis and how best to convey it to readers by using references to previously learned knowledge.

3) Retrieval

When you’re learning to speak a foreign language, the goal is to have the information available when needed. To do this, you must store the knowledge in your long-term memory and develop retrieval cues. These cues must relate the new knowledge to your previous learning and experiences.

For instance, a marine attending jump school must learn how to land safely to prevent damage. The first step for trainees is to practice falling from a standing posture while receiving positioning corrections. When they are two feet off the ground, they repeat the action.

As they fall from increasingly higher altitudes, the Marines apply their knowledge to each progressively harder level of difficulty, adding more complex skills at each level.

Similarly, every time you practice your target language, you generate a new experience giving you a fresh cue and helping you remember the information better.

Retrieval cues make it easier for you to access information in various circumstances, separating static facts from the knowledge that can be applied when the occasion arises. For example, you may recall information quickly with more retrieval cues.

Also, retrieving information from memory causes reconsolidation, strengthening memory traces. This enables you to make even more connections with the knowledge you’ve acquired since the information was first consolidated.

Your Brain Is Designed to Learn

Language Learning is a process that can last a lifetime. Your brain’s flexibility and plasticity allow you to learn new things and adapt to new situations. For instance, a blind person’s brain heightens their other senses to compensate for losing eyesight.

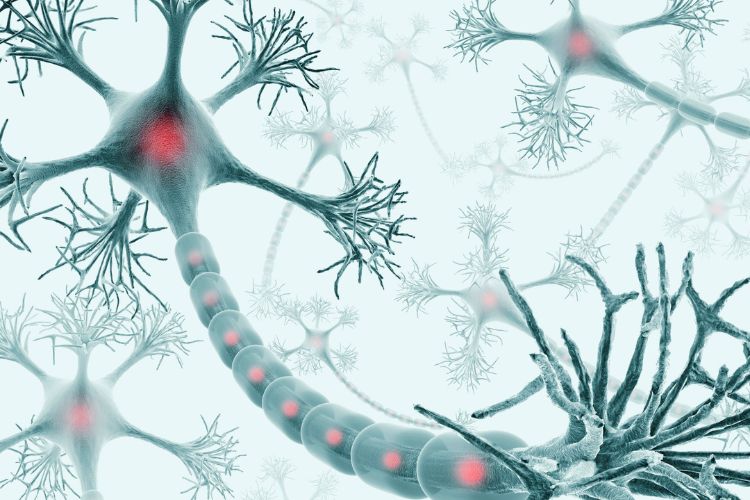

The Role of Neurons in Learning

Neurons, or nerve cells, are “the fundamental units of the brain and nervous system, the cells responsible for receiving sensory input from the external world, sending motor commands to our muscles, and transforming and relaying the electrical signals at every step in between.”

In essence, “the nervous system is a continuous loop of communication between the brain, spinal cord, and body and body, spinal cord, and brain.”

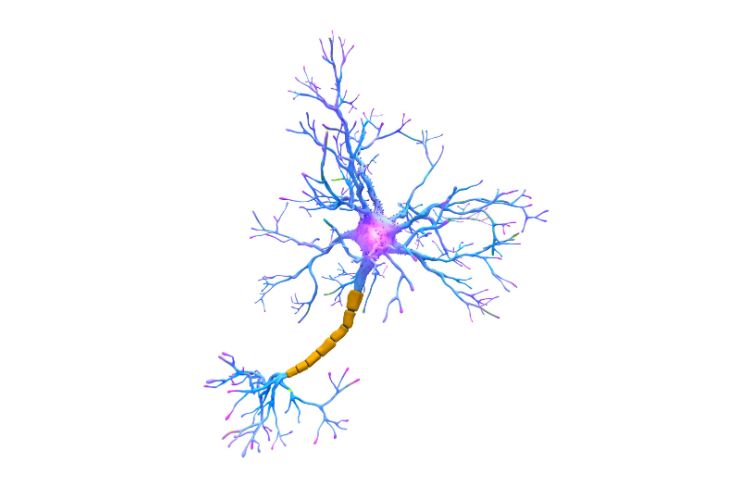

You possess millions of neurons, which are present at birth. Your neurons develop axons, which extend like branches to join with the dendrites, or receiving ports, of other neurons. Signals and information move along circuits called synapses. Synapses are the connections between axons and dendrites.

Myelin, a waxy coating on some axons, mimics the plastic used to cover the wires on electrical cords. According to scientists, the more you practice a skill, the thicker the myelin layer becomes on the connected axons.

As the myelin layer thickens, the signals needed to accomplish the skill get stronger and faster. This explains why professional basketball players’ dribbling synapses are so extensively myelinated after thousands of hours of practice that they can perform it reflexively.

Likewise, the more you study and practice the various components of your target language, the more myelinated those synapses will be for future use.

Experts argue that when a skill becomes habitual, your brain connects the motor movement and the cognitive action to happen instantaneously and unconsciously rather than through a conscious (albeit quick) mental process.

The habit is then recorded and retained in the basal ganglia, a region deep within the brain that controls eye movements and other unconscious behaviors. This is evident in the fact that many type on keyboards without paying attention to what their fingers are doing.

Neurogenesis and Neuroplasticity

Your brain keeps growing new neurons throughout your entire life—or neurogenesis. In language learning, the key to unlocking the full potential of your neurogenesis is to tap into your ability for plasticity.

Neuroplasticity is the state or capacity of the nervous system to change itself, whether in one’s conscious direction or as a result of unconscious adaptation to one’s environment. Adaptive plasticity, or self-directed adaptive plasticity, is a form of plasticity directed by an individual to improve and optimize the adult brain.

In short, the individual directs brain changes—primarily through focused attention during learning bouts—so challenging events and tasks eventually become reflexive behavior.

Dr. Andrew Huberman notes, however, “There are two aspects to plasticity: One is that there’s plasticity geared toward the thing that you are trying to learn specifically [such as a language], and then there are states of mind and body that allow us to access plasticity.”

He argues that sunlight and certain neurotransmitters play a significant role in human neuroplasticity and recommends viewing sunlight within the first hour of waking—ideally while walking, as it triggers the production of melatonin and cortisol approximately 16 hours later.

Melatonin and cortisol are hormones that affect sleep and circadian rhythms. Sleep is when the brain rewires and reconfigures itself after bouts of learning, resulting in greater long-term neuroplasticity. (Sunlight upon waking also provides an opportunity for short-term plasticity because it makes the brain more alert.)

He also argues the importance of three particular neurotransmitters: norepinephrine, acetylcholine, and dopamine.

Duration, Path, Outcome in Learning

Huberman distinguishes between reflexive behavior, which the nervous system performs nearly unconsciously or without much thought, and skills or “events” one is trying to learn, such as speaking a new language.

He describes unknown “events” the brain must figure out how to perform as, “duration, path, and outcome…the most stringent, high-focus regime for the brain.” These events often engender frustration, confusion, agitation, or stress in the learner during the learning process.

Such feelings signal that the brain is trying to figure out how to successfully perform the task, as the learning process produces an increase in neurotransmitter molecules, including norepinephrine, which can sometimes make it difficult to focus.

Improve Language Comprehension by Recognizing Underlying Principles

Let’s examine how to apply this knowledge and the techniques you can utilize to learn and study a language more efficiently.

Learning a new skill or concept, such as a foreign language, has two basic objectives:

- Comprehension: You must thoroughly comprehend how the fundamental aspects of the language apply to many circumstances.

- Retention: You need to retain the linguistic knowledge to draw on it later on with a more in-depth understanding when a problem or circumstance calls for it.

We’ll discuss how to increase your comprehension in this part.

Step 1: Learning the Rules

Simply memorizing facts from your textbook or lecture notes when learning a new linguistic concept results in a superficial understanding of the subject.

Instead, if you first discover the basic principles—the rules—you’ll learn more meaningfully. The rules will direct you when you apply this information to solve problems in the real world since they serve as the common denominators among various examples and settings.

Rule learners have an innate ability to identify the main ideas in classes and situations. Rule followers are adept at eliminating unimportant details to get to the essentials.

While example learners can recall individual examples, drawing out the fundamental ideas is difficult. As a result, they cannot deal with novel circumstances that differ from the examples.

How Students Who Use Examples Can Get Better

There are ways to improve so language learners don’t have to struggle. Studying numerous examples simultaneously, instead of just one at a time, might help you identify the common thread and draw out the underlying ideas.

Another approach is to compare and contrast two problems simultaneously to identify commonalities or discrepancies that would shed light on the rules and assist you in solving each challenge.

For instance, in two hypotheticals taken from research into rule learning, students were given these issues:

- A moat must be crossed by an army attacking a castle, but the bridges are built to blow up if too many people try crossing at once.

- Radiation therapy is the only option for treating an inoperable tumor. Still, the radiation doses required cannot eradicate the tumor.

Before looking at both and attempting to identify the similarities, the students struggle to answer each question when considered separately.

- Something huge is required to reach an objective.

- Disaster will result from using the entire force at once.

- While smaller sections of the force prevent tragedy, these sections lack the necessary capacity to resolve the issue.

When students draw out these parallels, they are likelier to devise a solution. A solution where they direct lesser pressures across several bridges or diverse radiation angles toward the target. Students can also use the answer to solve various problems if they understand their fundamental ideas.

As a language learner, you can apply this to your studies, for instance, by examining several different sentences in your target language, allowing you to see numerous examples of things like verb conjugations, vocabulary use, or particular grammar rules in a greater variety of contexts.

You can then draw parallels between the different sentences and their components, allowing you to more effectively understand the fundamentals of the concept you’re learning.

Build Up Your Language’s Structure with Mental Models

Once the rules have been determined, link the guiding concepts to any prior pertinent information.

This procedure, known as “structure building,” establishes the context and broadens your language comprehension. Developing mental models, combining related ideas or abilities into a flexible skill set, is another benefit of structure building. We will cover more on mental models later.

Aside from being skilled at understanding rules, high-structure builders can also tell when new information benefits their structure. Low-structure builders, however, have difficulty with these abilities.

How Low-Structure Construction Can Be Enhanced

Whether high-structure builders have a cognitive advantage that comes naturally or learn languages intuitively is a matter of debate among experts.

Whatever the justification, low-structure builders can enhance their language learning endeavors by implementing these strategies:

- Frequently pause when reading or listening to ask yourself the key ideas.

- Consider what you’re learning or how you used the information in a specific setting. Consider how you came up with a solution, what you might have done differently, and how you can get better the next time. A topic’s core ideas automatically crystallize when you reflect on it.

Mental Models

As we previously discussed, mental models combine information and abilities to produce more sophisticated abilities. Further, we can distinguish relevant information from the background noise of information using perceptual intuition.

Making accurate “quick judgments” is the essence of perceptual learning, fostering perceptual intuition. It involves reacting appropriately to our surroundings by focusing on the most crucial signals and disregarding the rest.

Although we do not naturally possess this skill, we can become specialists with enough practice and patience.

For instance, driving a car requires a wide range of knowledge and abilities. You must comprehend traffic regulations, be aware of how hard to step on the gas and brake pedals, and switch on your windshield wipers without looking away from the road. It may seem overwhelming to learn so many new skills at once.

Still, with time and practice, they will all come together to form a mental model allowing you to drive without consciously thinking about each move you make.

To learn how to drive a bus or a big rig, you may use your understanding of driving a car as a starting point. Similar to training a specific skill, using your mental models in various contexts helps you become more adept at using all aspects of your target language in different scenarios.

For one to become a master of a skill or subject, mental models must be formed. Experts in their fields—such as NBA players or professional musicians—practice for countless hours to develop mental models for every scenario that might arise. They may then quickly use any mental model they require in any setting.

Similarly, we can employ perceptual learning models to do the same.

In one study, medical students were instructed to quickly identify the type of lesion or rash in photos of various skin rashes that, to the untrained eye, appear to be identical. The students gradually mastered the art of instinctively diagnosing dermatological issues because these quick selections helped them “feel” the correct response.

You can also develop your perceptual intuition by using perceptual learning models in your language learning routine.

Improve Language Retention in the Brain

You’ve created a mental model using the main ideas from a lesson you’ve noted. You must now retain the knowledge.

Retrieval practice is the most efficient approach to increasing new information retention. Any exercise that challenges you to recollect the knowledge or skill you have acquired is called retrieval.

Retrieval practice may include:

- Taking a test that’s given in class

- Assessing yourself using flashcards

- Coming up with inquiries regarding important ideas to test yourself afterward

Consider studying to be like bead-stringing a necklace. Your memory is the string, and each new notion, information, or ability is a bead. If you don’t secure the beads with a knot, they will just fall off the other end of the string.

The knot keeps the knowledge you gain from being lost. You double- and triple-knot the string as you continually practice retrieval to prevent the beads from falling off.

The more you can recall information when needed, a crucial component of language mastery, the better your memory works. A quarterback, for instance, trains his movements and scenarios until they come naturally since, during a game, he won’t have time to pause and think about what he needs to do.

Let’s discuss the issues with the two methods that the majority of people employ—rereading and mass practice—before we go into how to optimize the advantages of retrieval practice for language learning.

Why Mass Practice and Rereading Fail

In a few days, you have a test or presentation, so you need to commit pages’ worth of notes to memory. How do you behave?

If you’re anything like the majority, you read the content and then reread it several times, perhaps underlining and making notes as you go.

Rereading and massed practice—doing one item repeatedly in a single sitting—are generally regarded as the most efficient methods for learning and memory.

But there are three issues with single-subject attention and unending repetition.

1) They are time-consuming.

Rereading takes time better spent on other, more efficient techniques, which we’ll discuss later.

2) They don’t aid in long-term memory retention.

You might retain new information long enough to pass the test the next day, but by the time the midterm comes around, you’ll have forgotten most of it. In reality, studies show that using these techniques causes retention to disappear rapidly.

As Huberman puts it, “It’s, ‘I want to know how to speak that language. I want to be able to do that skill. I want to be able to feel this way without having to put much work into it.’ And there are tools and protocols that one can [use and] do to achieve that.”

In a pair of similar studies carried out at two different colleges, one group of participants read the material once, while another group read it twice in one sitting. The group that read the material twice performed marginally better when both groups were evaluated immediately after reading.

The benefit of rereading was only fleeting, however, because there was no difference when the groups were evaluated later.

3) They make you believe you are an expert on the subject.

Repeatedly rereading a piece of material helps you become more familiar with it and how it functions, deceiving you into thinking you have grasped the ideas it seeks to convey. Understanding the material, the underlying principles, and how to use them in various contexts is necessary for mastery.

Can you convey a concept to someone else on your terms even though you may have understood it through a lecture or textbook? Can you think of another instance of this concept? Can you use this concept in another situation? Solely rereading does not reveal your understanding gaps.

Memorizing information through repetition is more effective than reading it. Instead of just rereading sections of a book, you should actively test your knowledge of the language if you want to get the most out of what you’ve studied.

One technique to achieve this is to explain the material to another individual. The connections between the neurons that retain your knowledge will become stronger due to the extra effort you put into discussing a particular subject, making subsequent information retrieval simpler and quicker.

Let’s now examine how retrieval practice can enhance retention.

Guiding Principles for Improving Retention in the Brain

Principle 1: Better Retention Results From More Difficult Retrieval

Some educators have a misconception that making learning and studying pleasurable and simple increases their effectiveness. Students must be learning if they are engaged and enjoying themselves, right?

On the contrary, your brain will better ingrain information into your memory if it must work harder to retrieve it.

Retrieval can be harder in two ways:

- Using generation, also known as generative learning, calls for you to devise the solution. Unlike true/false and multiple-choice questions, which provide possible solutions, flashcards, short-answer questions, and essay prompts use generation.

- Delaying retrieval practice makes remembering information more difficult for your brain. The gap should have passed long enough for your memory to become a little hazy but not long enough to relearn the content. The more time that passes between now and the first test, the more you’ll forget. However, studies suggest that after the initial retrieval practice, the forgetting rate slows dramatically.

In a study, participants remembered word pairs better when utilizing generation to determine which word was missing from each pair before filling it in.

For instance, after being given the clue “foot-s_ _e,” participants had to figure out that it should be “foot-shoe.” Despite the task being rather basic, participants’ recall was boosted by the extra effort of having to fill in the spaces rather than just reading the pairs.

Additionally, participants’ memory performed better on a follow-up test if they were given a word pair to start with and then had to fill in 20 additional word pairs before beginning their first retrieval exercise. Once more, the short delay made the initial retrieval more difficult, which helped retention.

In language learning, this concept can be applied to learning new vocabulary. Imagine trying to comprehend every word on a list and then returning a week later and trying to remember as many as possible.

According to studies, you’d have a 20% higher chance of remembering words that took a little longer to recall and a 75% higher chance of remembering terms that were particularly difficult to recollect after one week. Before placing them, the words on the tip of your tongue fall into a third group, which you’re twice as likely to remember a week later.

Therefore, the key is to remember a term just as you are about to forget it.

This information is used by the spaced repetition method to enhance long-term memory. The spaced repetition method instructs you on which words to practice when and how often to do so while using flashcards at various intervals.

According to memory studies, one month is the best time to recall a word to retain it long term, so this interval is used by most spaced repetition methods, allowing you to learn the term today and be reminded of it one month from now, right when you’re supposed to forget it.

This efficient approach may be applied to words and grammatical ideas. You may, for instance, learn 3,600 flashcards with 90–95% accuracy in just four months.

Utilize Generation and Retrieval for More Effective Learning

Use generation when first learning a language-specific concept by attempting to solve an issue before you know how to do so. Even if you choose the incorrect response, you’ll thoroughly learn the solution and remember it longer.

Regarding generation, remember the following:

- You rummage through your memory for any information that can help you find the solution, while you try to figure it out. For instance, if you’re seeking to identify the correct conjugation for a verb, you might start by listing all the conjugated forms you are familiar with, along with any relevant information. Your prior knowledge is already retrieved and ready to connect with new information when you discover the right answer—an essential component of learning and retention.

- When you struggle to solve an issue correctly, you are more attentive to the answer once you discover it.

Principle 2: Increase Retention Through Regular Testing

The timing of your retrieval practice, in addition to the difficulty level, impacts your language learning’s effectiveness. The best strategy is to test immediately—after a brief wait, as stated in Principle 1—and then do more tests at various intervals.

The longer you practice retrieval at regular intervals after the initial test, the longer your retention will last. Regular testing strengthens your learning, enhancing your capacity to use the language in many circumstances.

In one experiment, test participants were asked to listen to a story and recollect the 60 things mentioned.

Retention among several student groups demonstrates the effect of quick and frequent retrieval:

- When assessed immediately after hearing the narrative, students were able to recall 53% of the things, and a week later, they were still able to recall 39%.

- After a week, just 28% of the things were remembered by the students who weren’t assessed immediately.

- Students who took the test three times in the first week remembered 53% of the items the following week. (Note: The text does not state how often they administered the three tests.)

The following section will cover spaced practice in more detail.

Principle 3: Retention Is Assisted by Corrective Feedback

While pushing yourself during retrieval improves retention, certain errors are unavoidable. Corrective feedback is essential because it shields language students from recalling incorrect information and reinforces the right knowledge.

Furthermore, delayed corrective feedback improves recall compared to immediate input. For example, consider instant feedback, like learning to ride a bike with training wheels. When you receive automatic corrections, you start to rely on that help, preventing you from truly understanding and mastering the skill.

Implement These Strategies to Improve Retention in the Brain

Strategy #1: Enhance Performance and Retention by Reflecting

How can you use the retrieval practice concepts in your language studies now that you are aware of them? Reflection is one method.

Using the technique known as elaboration, in which you paraphrase the key concepts and make connections to your prior knowledge and experiences, you can reflect on a lesson from class by reading your notes or the text.

For example, consider everything you already know about Spanish grammar when reading a textbook on the topic. Finally, consider how your understanding of Spanish relates to the facts presented in the book.

Additionally, every event in the real world that calls for applying your knowledge and abilities concerning your target language presents an opportunity for you to enhance your performance and retention through reflection.

Consider these things after an experience where you applied knowledge: your strategy, performance, and room for improvement moving forward.

Mentally practicing how to use your knowledge will help it stick in your mind longer as you reflect.

Strategy #2: Incorporate Retrieval into Regular Quizzes in the Classroom

Another important component of retrieval practice in the foreign-language classroom is frequent exams and quizzes. While testing is frequently used to assess students’ recall, it is often disregarded as a method to promote retention. Small adjustments, however, can significantly affect pupils’ learning.

Students benefit by taking smaller exams more frequently, such as unit tests and quizzes with minimal stakes, instead of only a few large ones during a semester.

Besides increasing retention, this strategy has the following advantages:

- Increasing students’ attendance, concentration in class, and at-home study time because they know that an exam on the subject is coming up

- Reducing students’ test anxiety because each quiz or test has less of an effect on their final mark than if simply two major exams determined it (Note: Although not stated in the text, kids may become more accustomed to and comfortable with testing due to its regularity.)

- Assisting pupils in determining what they already know about the language and which subjects require extra study

- Assisting teachers in determining what material needs to be reviewed and what pupils already know