The Unique Perspective From Which Guided Immersion Evolved

This post serves as an initial introduction to a language learning method called Guided Immersion. The method is an evolutionary work-in-progress and is informed by a decade of experience teaching in the field. This experience is based largely on efforts to teach an endangered language–Circassian.

In addition to the challenges that accompany the learning of any foreign language, endangered languages come with their own additional obstacles, most notably:

- Teaching materials are limited or non-existent.

- Fluent individuals aren’t qualified to teach.

- Those qualified to teach aren’t fluent in the language.

- Research on effective teaching strategies doesn’t exist.

- Teaching facilities, both real-world and digital, don’t exist.

- Learners span across ages, abilities, geographies, and time zones.

- Often, the first language (L1) of learners is one of many. (For example, in the case of Circassian, L1s of learners include English, Arabic, Russian, and Turkish).

- It is difficult for learners to fit learning efforts or classes into their schedules regularly.

- Geographies, where the language can be innately observed, are rare and/or inaccessible.

- There is little incentive or need to study or acquire the language, such as a lack of economic benefit.

- The language isn’t prevalent in modern media or literature.

- There’s no obligatory or statutory requirement to use the language in everyday life.

- Language learners may sometimes face challenges or even ridicule for “wasting” time learning an endangered language.

- Minor mistakes when speaking the language are often also ridiculed, discouraging its continued use.

- Finally, even if a motivated learner achieves fluency or even mastery, there are few people, places, or opportunities to use the language on a regular basis.

Over the past decade, I have developed Guided Immersion in an attempt to address each of these points. In doing so, I have also leveraged the following research:

- The Natural Approach by Stephen Krashen (1983)

- “The Four Strands” by Paul Nation (2007)

- Total Physical Response, a theory by James Asher

- Teaching Proficiency through Reading and Storytelling (TPRS) by Blaine Ray

Although Guided Immersion was developed based on my experiences teaching a single endangered language, it may be used to teach a wide array of languages because it’s based on a broad spectrum of theories of language instruction.

Guided Immersion has evolved through four phases:

Phase I: Efforts to learn an endangered language to the point of fluency.

Phase II: Attempts to teach this endangered language to others.

Phase III: Research and application of a variety of teaching methods.

Phase IV: Integrative experience combining the first three phases, culminating in advancements on the part of the author and his students.

I should note that as Guided Immersion has evolved, so too has my own fluency. In certain domains, I am often mistaken as a native speaker of Circassian. Additionally, many learners following my method have gone on to achieve a high level of conversational fluency in relatively short periods of time.

The Core Tenants of Guided Immersion

This was the context in which Guided Immersion was first conceived and continues to evolve.

Today, some of the defining characteristics of Guided Immersion are:

- Guided Immersion takes an “80/20” approach to language acquisition by focusing on three levels of fluency: beginner (500 vocabulary words), intermediate (501–2,500 vocabulary words), and advanced (2,501–5,000 vocabulary words).

- The curriculum’s vocabulary selection and orders are based on a combination of frequency distributions (based on research on the English language) and the Common European Framework of Reference for Languages (CEFR) vocabulary scales. This approach balances high-frequency words with highly-helpful low-frequency words.

- The vocabulary selection is presented in the context of highly helpful phrases and sentences conveying a wide variety of use cases in everyday life (e.g., “Can you help me?” or “Pick this up.” or “Put that down.”).

- These phrases and sentences cover a broad array of grammatical structures but are short in length, complexity, and syllables, making them easy to recall.

- The phrases and sentences are also designed to be “mixed and matched” so that the learner can organically develop the ability to convey concepts of increasing complexity over time (e.g., “Can you put that down and help me pick this up?”).

- Verbs are placed at the center of all phrases and sentences, and they’re accompanied by nouns and adjectives that are commonly used frequently in conjunction with those verbs.

- All vocabulary is taught in context using phrases and sentences, but it is also reinforced out-of-context through the use of flashcards and/or fill-in-the-blank “Cloze” deletions.

- All the above (verbs, collocated nouns and adjectives, phrases, and sentences) are conveyed through a series of single-sentence “micro-stories.” In keeping with this mix-and-match approach, the micro-stories evolve to swap in/out nouns and adjectives, holding the verb constant while moving through the first-person, second-person, and third-person singular versions of each verb.

- By design (and necessity), Guided Immersion supports a variety of teaching and learning models, including:

- Real-time, instructor-led teaching (both in-person and remote)

- Asynchronous, instructor-led teaching (both in-person and remote)

- Self-study learning (via video instruction and/or computer application)

- Peer-to-peer, study and learning groups

- The content taught using Guided Immersion is presented through a linear, 5-day Spaced Repetition System (SRS) during a “loading phase.”

- The content is then reinforced through a non-linear SRS over subsequent time intervals, which is most easily accomplished algorithmically via computer application (but may also be done through a well-trained instructor).

All of the above are delivered through Guided Immersion’s Five-Factor Framework, which is explained in the next section.

The Five-Factor Framework

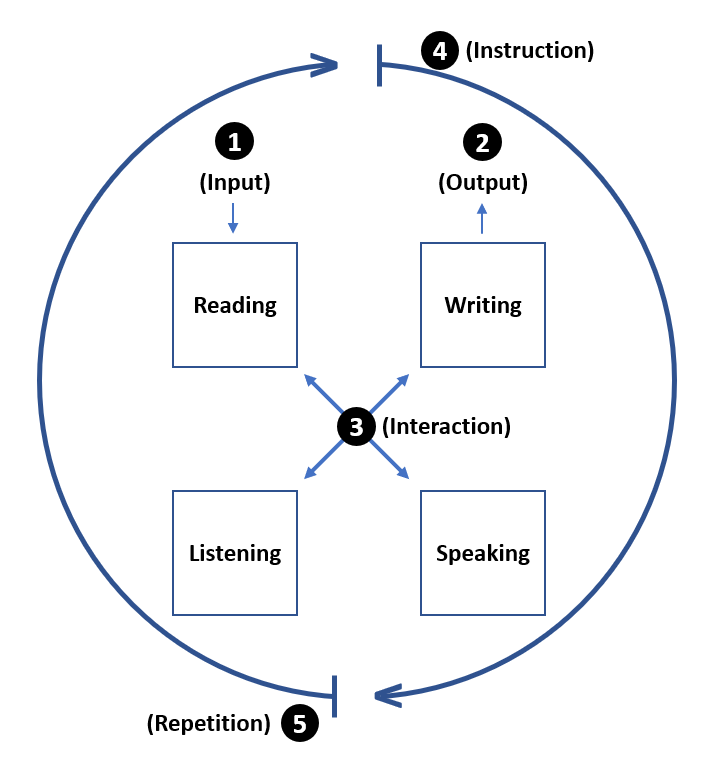

While the above explains the evolution and format of Guided Immersion, the components of Guided Immersion are explained here. Guided Immersion relies on its Five-Factor Framework.

These Five Factors are:

- Comprehensible input: Written or verbal messages that are meaningful, relevant, and understood by the learner.

- Grammatically correct output: Written or verbal messages produced by the learner that are grammatically correct and understood by a native speaker or instructor.

- Meaningful interactions: Written or verbal communication between the learner and a native speaker or instructor. These interactions should be in a context relevant and of interest to the learner (e.g., interesting stories or facets of everyday life).

- Formal instruction (study): The deliberate instruction and/or studying of technical aspects of the language (e.g., grammar, vocabulary memorization, etc.).

- Practice & repetition: Repetition of the above components over time, preferably with an SRS.

Language Learning Activities

Guided Immersion makes use of over 20 different language learning activities. The learner is encouraged to expand, customize, and innovate with this list of activities.

Comprehensible Input:

Reading |

1. Intensive reading |

Reading and looking up unknown words |

Reading |

2. Extensive reading |

Reading and guessing unknown words through context |

Reading |

3. Narrow (focus) reading |

Reading in a narrow area of interest |

Listening |

4. Listening while reading |

Listening to an audiobook while reading |

Listening |

5. Transcription |

Writing out what is listened to |

Listening |

6. Extensive listening |

Listening and guessing unknown words from context |

Grammatically Correct Output:

Speaking |

7. Prepared talks |

Memorization and practice of short discussions |

Speaking |

8. Reading aloud |

Reading and speaking aloud the words read |

Speaking |

9. Back-chaining |

Technique for practicing and improving pronunciation |

Writing |

10. Delayed copying |

Writing what was read 30–90 seconds later |

Writing |

11. Writing practice |

Writing (or re-writing) a prepared text or writing within a narrow domain by stitching together previously learned vocabulary or phrases |

Writing |

12. Extensive writing |

Writing within the known vocabulary and grammar |

Meaningful Interactions:

Read/Write |

13. Tandem pen pals |

Writing back and forth with a language partner, correcting one another’s writing |

Read/Speak |

14. Mini stories |

Participation in a Guided Immersion mini story |

Listen/Write |

15. Summarization (written) |

Listening and writing a summary of what was heard |

Listen/Speak |

16. Summarization (verbal) |

Listening and verbally summarizing what was heard |

Mix |

17. Free discussion |

Discussion of any topic, free of worry about speed, pronunciation, or grammatical mistakes |

Mix |

18. Roleplaying |

Character-based discussion within a defined context |

Formal Instruction:

19. Grammatical instruction |

Formal instruction of grammatical points |

20. Memorization |

Memorization of vocabulary and/or phrases |

21. Spelling practice |

Practice spelling of vocabulary and/or phrases |

22. Reading: 3/2/1 |

Reading a short text 3x, twice silently, once aloud |

23. Writing: 1/2/3 |

A 3-step writing process: 1) outline, 2) draft, 3) final |

Practice & Repetition:

| Continued practice & repetition of any and all of the above |

1. Intensive Reading

To read intensively is to completely deconstruct a text in order to absorb as much meaning as possible from it. This is accomplished by systematically looking up every word, phrase, or collocation in a text you don’t understand.

This is a mentally demanding and time-consuming activity.

As a result, learners who engage in intensive reading must be careful to adhere to specific guidelines or risk boredom and burnout.

If you want to read a text intensively, you should choose texts that are interesting and short, read for short periods of time, and read when you have the most mental energy.

2. Extensive Reading

Reading extensively means simply reading as much as possible without concern for the nuance of meaning or the occasional unknown word.

This is accomplished by reading for long periods of time and only looking up words when absolutely necessary to your comprehension of the text.

If the text you want to read extensively is at the appropriate level, you’ll find that most unknown words can be deciphered by looking at their context, eliminating the need for translations or dictionaries.

While intensive reading requires a high level of concentration and deliberate effort, extensive reading is intended to be a fun and pleasurable experience that requires little mental effort. The more you read, the more language you are exposed to, allowing you to quickly increase your passive vocabulary knowledge.

3. Narrow (Focus) Reading

Narrow reading refers to reading that focuses on a single topic or subject area. It has three major benefits for language learning.

- It has the greatest impact on reducing the total number of different words to which the learner is exposed.

- Having a wide range of topics results in a diverse vocabulary and many more words that appear only once in the texts.

- By staying within the same subject area, the learner accumulates a wealth of useful content knowledge, which makes reading easier and, thus, guessing unknown words from context easier.

Narrow reading can be accomplished by (1) reading within a specialist area of knowledge, preferably one of personal interest, or (2) reading newspapers in the same story or general topic area.

4. Listening While Reading

The learner in this activity listens to a recording while silently reading the same text. This activity makes use of one skill (reading) to support another (listening).

Learners prefer listening while reading to listening alone; reading while listening results in higher vocabulary learning and comprehension-related scores.

5. Transcription

Transcription entails making a recording of a short, spoken text on a relevant topic and replaying it many times while attempting to write it down.

The text should be brief, perhaps only 100–200 words. The learner is encouraged to pause, rewind, and re-listen to the recording as many times as necessary in order to deconstruct it for transcription purposes.

This intentional learning activity improves listening skills while also providing useful feedback on word and phrase recognition.

6. Extensive Listening

Similar to extensive reading, extensive listening is the practice of listening to spoken language as much as possible and trying to follow the general meaning.

This is best accomplished by listening for relatively short periods, perhaps 2-4 minutes, and re-listening as often as required to ensure one has a general sense of what is being discussed.

7. Prepared Talks

In this activity, the learner writes out sentences or phrases that are of personal importance and relevance. These phrases and sentences should be checked for proper spelling and grammar, and the learner should take care to understand the proper pronunciation of this content.

The learner is then encouraged to memorize these short sentences and phrases, using them as anchor points in written or verbal communication.

Below is a list of topics that may be relevant to this activity:

- The weather or daily events

- Oneself, family, hobbies, or interests

- Purpose of learning the target language

- Movies, TV programs, or current events

- Asking or giving directions

- Topics of transportation

- Visiting a restaurant

- Asking for help (or to slow down)

8. Reading Aloud

Reading aloud is a very straightforward activity, and many new language learners do it subconsciously, albeit at a low volume.

One simply acquires an appropriate level of text and reads it aloud—at a low or moderate volume. The goal here isn’t necessarily to practice pronunciation but to improve overall comprehension.

9. Back-Chaining

Back-chaining is a technique that helps the learner improve his or her comfort and pronunciation—especially with polysyllabic or difficult words and phrases.

As the name implies, with back-chaining, the last syllable is pronounced first, and the learner then works backward from the end of a word to the beginning.

It’s unclear precisely why back-chaining works, but one theory is that it reduces stress on the part of the learner. Back-chaining may be applied to individual words, short phrases, or whole sentences.

10. Delayed Copying

With delayed copying, the learner selects a useful and relevant text around 200 words long (about 20 lines). This text is read with the intent to be understood. A dictionary may be used if necessary.

The learner is then encouraged to focus on the first few words of the text, hold them in memory, and remove the text from visual reference.

The learner then sets about the task of attempting to recreate the full text from memory. The benefit of the activity comes from trying to hold longer and longer phrases in mind before writing them down.

This deliberate learning activity improves typing (or handwriting) skills and memory for phrases.

11. Writing Practice

In this activity, the learner takes an existing text known to him or her and well-understood. This text should be of intermediate length, perhaps 250–500 words.

The learner is then encouraged to write a short essay, no more than a few sentences long, within the topic or context of the text.

The learner is encouraged to use as many vocabulary words and/or grammatical structures as possible, borrowing generously from the reference text but creating a new piece of content.

This allows the learner to build on known vocabulary and grammatical structures to produce new content that is as grammatically correct as possible in written practice.

12. Extensive Writing

With extensive writing, the learner is encouraged to engage in free-form writing on any topic of interest to him/her. The activity should be enjoyable and not burdensome.

As such, the learner is encouraged to stick to a topic of personal knowledge and interest and to keep the written text relatively short.

The learner shouldn’t worry about spelling or grammatical correctness. Part of the challenge is to convey one’s thoughts using only the vocabulary and grammatical structures known to the learner.

13. Tandem Pen Pals

This activity works best when the learner is paired up with a language learning partner who is a native speaker of the learner’s target language and wishes to learn the native language of the learner in question (e.g., an ideal pair might be a native English speaker who wishes to learn German and a native German speaker who wishes to learn English).

On a regular basis, each learner would be given a “getting to know you” question and asked to write a few sentences, perhaps 5–10, on the topic.

Writing would be done in the target language each pen pal wishes to learn (e.g., the native English speaker would write in German, and the native German speaker would write in English).

The pen pals would then share these texts, and each would correct the other’s mistakes. This might be done in real-time through discussion or asynchronously through the use of the “tracked changes” feature in programs like Microsoft Word or Google Docs.

14. Guided Immersion Mini-Stories

As the name may imply, Guided Immersion mini-stories are unique to Guided Immersion and most often delivered in an instructor-led setting. Self-study is possible, so long as the learner has access to the content necessary to construct a mini-story.

The story is centered around a single, short sentence, often in the present tense, around a high-frequency verb. The sentence illustrates a third-person (singular) character doing the activity of the verb.

The learner is then given the proper conjugation of the verb in the first and second person (singular); characters that are doing variations of the verb’s activity are introduced, as are high-frequency, co-located adjectives and nouns.

The learner (or instructor) then constructs a story that uses all of the aforementioned content.

Guided Immersion mini-stories are powerful, as they allow for all the ingredients necessary for grammatically correct interaction. However, aside from a single sentence, the learner is responsible for constructing the grammatically correct statements (or questions).

15. Summarization (Written)

In this activity, the learner selects a short text or audio file. The text should not be more than 500 words but not less than 150 words. If an audio file is selected, the total length should not be more than 2–3 minutes in length.

Once the content has been consumed, the learner then does his or her best to write out a summary of what s/he understood and recalled from the content in question.

16. Summarization (Verbal)

This is the verbal analog to written summarization. Again, the learner selects a short text or audio file. The text should not be more than 500 words, but not less than 150 words. If an audio file is selected, the total length should not be more than 2–3 minutes in length.

Once the content has been consumed, the learner does his or her best to verbalize a summary of what s/he understood and recalled from the content in question.

17. Free Discussion

As the name implies, in this activity, the learner engages in free verbal discourse on any topic or subject. There are no set rules or boundaries as to which topics may be suggested, but it’s advisable that the topic is known to the learner and of interest.

In this activity, there are only two rules:

- The learner need not worry about pronunciation or grammatical correctness. The goal is to develop comfort in communicating.

- The instructor or other learner who is conversing with the first learner should avoid the temptation to correct any errors the learner might make. Probing for meaning is welcome, but corrections of grammar or pronunciation are discouraged.

18. Role-Playing

Role-playing activities involve two or three people acting out the parts in a common situation. For example, going to the doctor, shopping, getting directions, ordering food in a restaurant, and striking up a conversation with a stranger.

Each member of the pair or group assumes a different role and acts out the situation. At the end of each role-play, the participants should discuss how they could improve on what they just did. Then they should immediately repeat the role-play with the improvements.

If you can do it a third time immediately after that, that would be helpful. The same role-playing exercise should be repeated two or three times in subsequent sessions.

19. Memorization (Vocabulary, Phrases, and More)

Rote memorization has its place in language learning and can be very helpful in developing vocabulary and command of key phrases. Memorization may be done through a variety of means and through several different approaches.

Learners may opt to write out words or phrases, use physical flashcards, or make use of a flash card computer program.

At the same time, learners may select to memorize vocabulary in the context of short sentences; by linking vocabulary or phrases to other, previously learned concepts; or by means of images or “memes.”

20. Grammatical Instruction

Activities that fall under the banner of grammatical instruction entail the deliberate teaching of grammar points of the target language.

However, in each case, the learner should avoid the temptation to memorize specific rules. Instead, the learner should approach grammar as a pattern that helps explain how and why the target language operates the way it does.

Additionally, grammatical principles should be learned in the context of many real-world examples.

21. Spelling Practice

This is a fairly self-explanatory activity. The learner practices spelling words, short phrases, or simple sentences.

This may be done in several ways. The simplest might be to write or print out the content to be practiced on a sheet of paper, cover each piece of content, and then attempt to write it out.

A similar approach may be done with a computer and a keyboard. Once the writing (or typing) is complete, the learner can review his/her work and compare it to the reference content. Errors should be identified and marked for future practice opportunities.

22. Reading: 3/2/1

In the 3/2/1 reading activity, the learner reads a text three times—twice silently and once aloud. Texts should be anywhere between 150 – 500 words. The first time around, the learner reads extensively and avoids dwelling on unknown words. The focus should be on well-known words.

The second time around, the learner reads again and spends more time on the unknown words.

Again, reading is done extensively, and the learner tries to guess the meaning of unknown words through context or word roots. (The learner is free to look up unknown words if desired, but it’s not necessary for this activity.)

The third time, the learner reads the text aloud, practicing pronunciation.

23. Writing: 1/2/3

In the 1/2/3 writing activity, the learner is encouraged to take a structured approach to writing a short text. The text might be as short as a few sentences or as long as several paragraphs. This is entirely up to the learner.

In the first step, the learner thinks through what s/he wants to write and identifies keywords conveying the main points of the story.

In the second step, the learner composes a high-level outline that fleshes out the keywords into rough thoughts. In the third and final step, the learner sets out to write out the entirety of what s/he wants to convey.

The learner shouldn’t dwell on grammatical structures or vocabulary words that are unknown but should develop a comfort level articulating him/herself within the confines of known grammatical structures, vocabulary terms, and/or phrase structures.

Using Guided Immersion

You’ve made it this far, so I assume this post has been helpful to you. I’ve covered plenty of different concepts and practical tips to send you on your way.

Of course, I sell a product, and it incorporates everything I’ve written in this post. I think it can be helpful for lots of people, including you. If what you’ve read has been beneficial to you, I’m confident my OptiLingo system will be as well. So, here it is in a nutshell.

Guided Immersion Is the Key

Different language-learning companies use different approaches. After extensive research on the subject and spending years teaching myself one of the most ancient and difficult languages on the planet–Circassian–I developed my method for learning a new language.

Guided Immersion employs a proven method that turns the old way of language learning on its head. Instead of “memorizing,” we emphasize “remembering not to forget.”

Here’s how:

- By teaching you useful phrases and high-frequency words, presented in a low-stress environment, with spaced repetitions and built-in reviews.

- By making every phrase short, easy to remember, and interchangeable with every other phrase.

- By embedding more than 1,000 of the most common words, which account for over 80% of spoken language, into these phrases. This approach is at the core of Guided Immersion.

In short, Guided Immersion works, and it works quickly.

I believe you’ll love Guided Immersion as much as I do. It’s what I used when I taught myself Circassian. If you’d like to know more about how I did that and my personal background, check out my bio online.

The only real requirement necessary for Guided Immersion to work is that you relax and enjoy yourself throughout the course of your studies. The most important factor in learning a language—beyond deciding to learn—is that you don’t allow yourself to be scared or intimidated.

Leave any anxieties or tensions behind. While you’re at it, try to clear your mind and put aside distracting thoughts. The key here is to avoid the temptation to try memorizing or studying the material being presented.

I know that sounds counterintuitive, but remember the difference between studying and learning? The responsibility for your success lies with the course and how it was designed. Put your faith in the Guided Immersion process and free yourself of the pressure and anxiety that come from studying or memorizing.

Let the information be absorbed naturally, and it will become knowledge you will never forget!

You may be tempted to memorize vocabulary words, and for some, that might be OK. But the vocabulary terms in my course are provided to add greater context to language structure, and you needn’t memorize them.

Your regular reviews of each lesson will ensure that these terms, and the phrases in which they appear, etch themselves into your memory in an organic and graduated process.