Lots of people say they’d like to learn a second language. Why is it some people never start, others start and quit, and others reach their goals? Some people want to learn a language but believe they aren’t able to do it. As a strong advocate for language learning, nothing is more painful for me to hear.

Anyone can learn a language! And in this piece, I want to debunk language learning myths and then look at why people fail. If we’re aware of the most common potholes, we can avoid them and set ourselves up for success.

You Can Easily Learn a New Language

From my point of view, the worst reason for monolingualism is “I am just not good at learning a language.” That’s like saying, “I am just not good at walking or eating” because learning a language is as natural and common as any other human function.

If you’re reading these words, you’ve already learned at least one language: English. Had you grown up in China, Saudi Arabia, or Brazil, do you doubt that you would be fluent in Mandarin, Arabic, or Portuguese? With the exception of a very few savants, there is very little that makes any human being more or less predisposed to learning a new language.

The simple truth is that everyone is good at learning a language. Since nearly every human being is able to speak at least one language. This is a fact. An equally factual statement is that anyone can learn a second or third or tenth new language.

Why People Fail to Reach Fluency

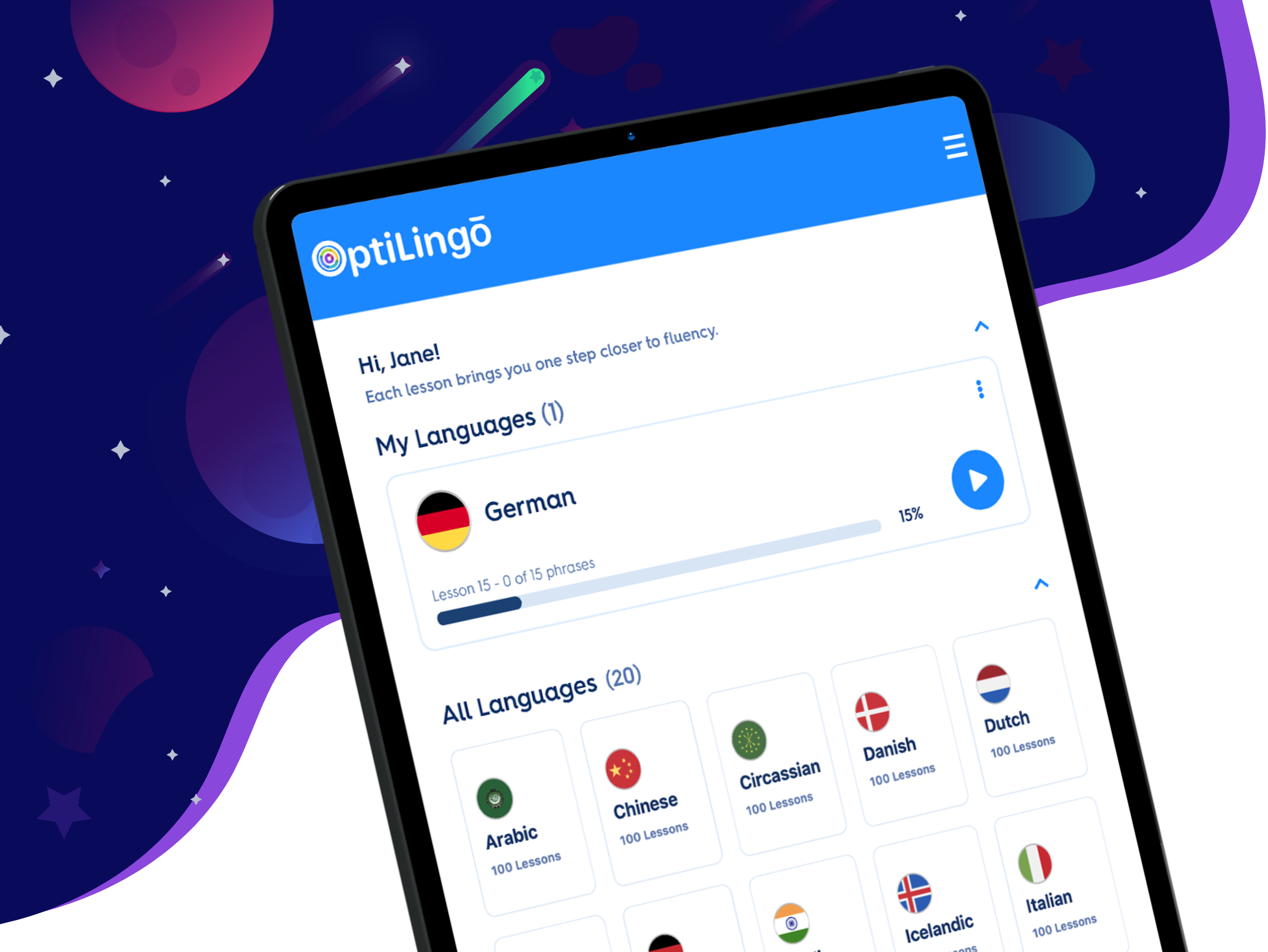

We are in a golden age of language learning. Never before have there been so many tools or such great interest in learning new languages. From Spanish to Klingon, there have never been so many opportunities to learn a new language.

So why are we not living in a utopia of polyglots? Why do we continue to see the average number of languages spoken by the typical English speaker hover at 1.x?

It’s because so many people fail at language learning. In fact, I’ll even go out on a limb and say that perhaps most people fail at language learning. While that’s a bold statement, it’s not particularly controversial. Nor is it insightful.

The more interesting question is this: why do people fail at language learning?

The answer is so simple and straightforward that you may be underwhelmed.

People fail at language learning for one of five reasons:

- They do nothing.

- They have unrealistic expectations.

- They have bad experiences.

- They do the right things but in the wrong way.

- They do the wrong things but in the right way.

Successfully learning a new language comes down to four variables:

- Content

- Methodology

- Time

- Consistency

Paths to Avoid If You Want to Learn a New Language

We’ll come back to those four variables. But first, let’s discuss the most common ways language learners run into trouble.

People fail when they do nothing.

I want to learn a new language.

I want to get in shape.

I want to be rich!

How often have we heard statements like these? How often have we said them ourselves? How often have we followed through? The vast majority of people who fail at language learning do so because they do nothing to achieve their goal.

Sure, maybe they download an app or buy a book. Maybe they make a plan to memorize a set of words. But these are not meaningful efforts, and many of them do more to alleviate the guilt of inactivity than they do to advance the goal of learning a new language.

I’m not judging people who fail to take meaningful action. There are a number of reasons why people may do nothing. It might not be the right time. They may not be mentally ready. They might have too many other obligations or commitments that take priority.

That’s all fine. I’ve been there myself. I think we all have. The description here is not meant to castigate people who do nothing but to honestly and objectively define one reason why people fail.

Three Reasons Why You Can Do It

If we understand why people don’t learn a language, we can work to overcome it. The dream of language learning is far easier to foster than the effort necessary to achieve success. But if you’re serious about learning a new language, you need to make sure that you meet three criteria.

You have the Time to Learn a Language

Are you working two jobs and putting yourself through school? Maybe you have lots of family commitments or do volunteer work. Perhaps you work a single job and come home exhausted every night. That’s life, and there’s nothing wrong with any of these situations. But if you are serious about learning a language, you’ve got to make sure you have the time.

You Have the Right Language Learning Goals

Are you able to sit down and focus on your daily language learning efforts? Are you able to find a calm, quiet place to do so, or are you distracted by work or family matters? Perhaps there is an aging relative whose health is a concern to you. Learning a language requires a lot of mental activity. And if you are unable to focus on your daily studies, you’re likely wasting your time.

You Don’t Have Competing Obligations.

I don’t know about you, but I’m married with four children. I also have a number of personal, business, and non-profit obligations. All of these commitments compete for my time. I don’t view any of them as burdens, but they do leave me with competing priorities. I don’t always get a chance to attend to my own language-learning studies as often as I would like. But that’s life.

If you’ve got competing obligations, that’s fine. Go attend to them, or reprioritize, if you are able to.

The bottom line is this: while there are many lazy people in the world if you’re reading this, you’re probably not one of them. Don’t beat yourself up if you’re failing at learning a new language because you’re not taking meaningful action toward that goal.

Think hard about what’s holding you back and ask yourself an honest question: Is now the right time? If not, why not? If not, are there changes I can make in my life that would free me up to commit to learning a new language?

Remember, even if now is not the right time, you don’t have to give up on the dream.

Unrealistic Expectations Prevents Foreign Language Fluency

Many people decide they aren’t good at learning languages when they try and don’t succeed as quickly as they expect. Anything worth doing takes time and effort to learn. It typically takes a baby about a year to learn to walk and another six months to learn to run. The more complex the skill, the greater the time and effort required.

At the same time, no matter how valuable or intricate the skill, it is surprisingly easy to pick up the basics. While it may take babies a year to learn how to walk, in their earlier efforts, they typically advance from crawling to “toddling” within a matter of weeks. The real-time and effort comes from making sure they are well balanced, don’t fall, and ultimately learn how to run.

Likewise, most people can learn a few guitar chords (or piano chords or drum beats) in just a few minutes. They might even develop a comfort level in a few hours. But being able to play a broad range of music, improvise, or write new music can take years.

Language learning is no different. You can pick up some essential phrases of a new language in less than an hour. But if you want to carry on a conversation of any depth, it’s going to take more effort and commitment.

Most Language Learners Fall into 2 Categories

At this point, most people fall into one of two groups: those who dramatically underestimate the amount of time and effort necessary to learn a new language, and those who dramatically overestimate.

The former often get stuck or discouraged, plateauing early on in their language learning efforts. The latter frequently fail to even begin, or start and take such an over-engineered, onerous approach that they rarely make much progress.

These misperceptions are often amplified by the explicit or implicit statements made by language learners and/or companies that sell language learning courses.

Misinformation Can Prevent You From Reaching Your Goals

Of course, the sellers of language learning courses want to put their best foot forward, and I’m sure they all believe they really have developed a course that is “simple and easy.” There is nothing misleading or unethical about statements like these, and the majority of course providers are reputable and honest.

Moreover, most courses produce a reasonable level of success. So long as the language learner sticks with them, and more importantly, the courses are aligned to the personal styles, goals, and schedule preferred by the language learner.

Likewise, the vast majority of language learners sharing their experiences are also reputable and honest. Whether it’s a blogger, YouTube video maker, or someone you know, very few language learners try to mislead others.

Your Attitude Impacts Your Results

However, far too often, most people view polyglots the way we view competitive athletes. They see the end result of hundreds or thousands of hours of hard work and forget how much effort it took to get there. Or worse, we assume it’s “just a natural gift.” Either way, we consume unrealistic expectations along with what we read or view.

All these attitudes can lead people to believe they aren’t good at learning languages before they even begin. Even the way we talk about our desire reveals what we expect.

Let’s go back to our initial statements of intent:

I want to learn a new language.

I want to get in shape.

I want to be rich!

I try to avoid statements like “I want to X.” They’re on the same level as “I want a cookie,” and their achievement is a function of how easy the terminal task is to accomplish. Such statements lack action, power, or inspiration.

Further, learning a language is not a terminal task. There is no endpoint where you’re done. This is even the case with your native language. We are always learning and growing.

I prefer to say, “I am learning a new language.” This is action-oriented and open-ended, and it conveys a strong intent and realistic expectation.

Bad Language Learning Experiences Cause People to Fail

Another force that drives many people to believe they are not good at learning languages stems from bad experiences–and unfortunately, there are many of them. Below are a few of the most common.

Being Forced to Learn a New Language

Many of us studied a foreign language in grammar school, high school, and/or college. We’ve often heard something like, “I studied Spanish for years, but I don’t speak it.” Alternatively, you may have studied a heritage, ethnic, or religious language after school or on the weekends. We’ve also probably heard something like, “I studied Hebrew for 10 years, and I could barely get through my Bar Mitzvah.

Of course, these are broad-based statements. There are many people who successfully learn a foreign language at school or in after-school programs. But how many of these students study these languages because they truly want to, and how many because they are forced?

I was forced to study Arabic for 12 years. But, I was far more interested in watching cartoons. It was only later when I decided I wanted to learn, that I made any real progress.

People who are forced into an activity rarely do so with much zeal or passion. And it’s nearly impossible to make progress without these incentivizing factors. This is especially true with language learning.

Dealing with Bad Foreign Language Teachers

I truly believe that the vast majority of teachers have only the best of intentions. But in any large population of professionals, there will be people who are great, people who are not so great, and everything in between.

From a mathematic perspective, one out of every two people in any given population will be below average. Thus, there are bound to be bad teachers out there, and regardless of the subject, we’ve all had at least a few of them.

These may include public school teachers, university professors, private tutors, or amateur language-teaching enthusiasts. While we call them “bad” here, in most cases they are not “bad” in the sense of being evil. They are not even necessarily “bad” in that they are poor at their jobs.

In most cases, they are “bad” because their teaching method is not aligned with the preferred learning method of the student. Perhaps the “bad teacher” is more visual, while the learner is more auditory. Perhaps the “bad teacher” likes to use content related to history, while the learner prefers content related to culture.

There are lots of ways in which the teaching and learning method might not be aligned. But the end result is almost always the same: we walk away feeling disenfranchised by a “bad teacher.”

Using Bad Methods Can Keep You From Fluency

Other times, language learners are exposed to bad methods. Sometimes these bad methods might be employed by bad teachers, so the language learner gets a “double whammy.” Other times, the bad method might be used by a language learner who is trying to learn through self-study.

Here again, the reasons why a method might be “bad” are similar to the reasons a teacher might be “bad.” There are dozens of methods and/or activities that one might use in either a classroom or self-study environment. While I personally believe that some are better (or more time-efficient) than others, there are very few methods that absolutely won’t work.

In contrast, there are probably many, many methods that won’t work for you. Some people love to write out words and phrases at regular intervals. Others prefer the ease and portability of apps. Some people like to listen to and repeat the audio content. Still, others like to translate short articles to and from their target language.

Most people new to language learning fail to realize how many different methods, approaches, or activities are available. They are tempted to believe that there is one method or one book or one app that will “get them fluent.”

At the same time, many language learners mistakenly believe that language learning is a task, chore, or job that needs to get done. They don’t appreciate that language learning can and should be an enjoyable experience. As such, they often fail to realize that some methods, like watching movies or playing video games in your target language, are valid study methods.

The Role of Timing When Learning a New Language

The final bad experience shared by many people stems from beginning their language learning efforts at the wrong time or place. To be clear, it’s possible for all of these bad experiences to overlap, but if you’re fully committed, with the best teachers and best methods, it’s still possible to have a bad experience if you’re starting at the wrong time or place.

The reasons why it may be the wrong time are many. Maybe your personal life is a bit complicated at the moment. Perhaps work is mentally taxing, and you can’t find time to devote to your language learning efforts. Or maybe you can find the time, but you just can’t focus.

Alternatively, maybe your work or home environment is just not conducive to studying. Or perhaps you have the time, place, and focus to study, but you can’t find native speakers or materials where you are located.

Taken in total, it boils down to this: lots of people – perhaps even most people – fall victim to the belief that they are not good at learning languages. Nothing could be farther from the truth. Anyone can learn a new language – including you.

Roadblock to Fluency: Doing the Right Things, in the Wrong Way

So you’ve decided that the time is right: you can commit yourself to learn a new language and you’ve set up a daily study schedule. Every day, for 30 or 45 or even 60 minutes, you can find a calm, quiet place to study. You’ve cleared one of the biggest hurdles, and you have the personal discipline and ability to study every day.

And yet you are still failing to reach fluency. Why?

There’s no simple answer here, but it’s because there is a mismatch between you, your preferred learning style, and the approach you are taking in your studies. Let me give you an example.

Below are a series of things you could reasonably do in order to advance your language learning efforts.

While I don’t personally care for some of them, they are all valid actions that work for certain people. But the devil’s in the details on a bunch of different levels. For instance:

- Using a textbook: Who wrote it? Is it appropriate for your skill level? Was it designed for self-study? Is the material fun, engaging, and/or relevant to what you want to learn? Are you forcing yourself to complete chapters that don’t get you closer to your language-learning goals?

- Engaging with native speakers: who are the native speakers? Do they realize you are just learning the language? Do they care? Do they have the time to care?

- Using video or audio: are there subtitles? Are they in the target language or in English? What is the content of those videos or audio? Is that content personally of interest to you? Is the material presented too quickly? Too slowly?

The worst-case scenario here is when you have the drive and discipline to commit to your studies, but you end up forcing yourself to study something that’s just not working for you personally.

Again, there are no black and white “always” or “never” rules here. But failing because you’re doing the right things in the wrong way can be dangerous. Not only are you losing time, but you run the risk of language learning burnout. As a result, you can become cynical, or jaded, and you may lose hope in the dream of learning your new language.

Language Learning Methods Matter

While the words here sound a lot like the words in the previous reason, the causes and effects here are fundamentally different. As noted above, there are plenty of things that can work, depending on your personal learning style and preferences.

At this point, you might expect me to say there is a shortlist of “wrong things” that will never work. But, I’m not going to make that claim. There are wrong approaches, and I think far too many people pursue them, but they are not wrong because they don’t work.

Here’s the secret: they are wrong because they are inefficient.

You may be someone who excels using language-learning apps. Or you may excel by studying a physical textbook. Perhaps you study both every day, but you’re failing. You may be doing the right things in the wrong way.

But what if the content and method you’re using are just very inefficient? What if the app you use has a bad algorithm for teaching (one that is not very time-efficient)? What if that inefficiency is compounded by the fact that it teaches you unhelpful, artificial sentence-based content like “Bears don’t wear pants”?

That’s not a collection of words you are ever likely to hear, read, or say when engaging with native speakers. At this point, you might be wondering how you can tell the difference between the right/wrong things vs. the right/wrong way. The answer is: you can’t.

At least you can’t at this stage of your language-learning efforts. If you’re a seasoned language learner–if you have three or four languages under your belt and you’re working on your fourth or fifth–then you can tell in an instant when something is right or wrong.

But chances are people like that aren’t reading this. It’s more likely that you’re focused on learning your first or second new language, and you’re worried about wasting time, money, or effort.

I understand these perspectives because I’ve wasted considerable time, money and effort trying lots of the wrong things. I’ve spent even more time, money, and effort dissecting why I think they are wrong, which is a big part of why I decided to write this guide for you.

What Are the Right Methods and Strategies?

Rather than going through all the wrong things and wrong ways to learn a language, let’s revisit and expand upon the four variables that define the right things and the right way.

- Content

- Methodology

- Time

- Consistency

You Need the Right Language Learning Content

This is far and away from the most important variable. What you study is far more important than the methodology you use.

- Are you a healthcare professional who wants to learn Spanish so you can speak with patients in a hospital? Don’t waste your time on travel phrases, and don’t be concerned with cursive writing.

- Are you working in a daycare with lots of Russian-speaking children? You should be focused on “sight words” like primary colors and parts of the body. Reading short children’s stories should be part of your efforts.

- Are you preparing for a business trip to China? You might want to focus on greeting and departure phrases. You may also want to pick up a few toasts and expressions of good luck and fortune. Finally, exposure to customs and cultural norms may be a big part of your study, as this might help you understand how, why, when, and where to use those toasts and expressions of good luck and fortune.

In each case, the content you study is intimately linked to the goals you have for your new language. I’ve met many people who are conversationally fluent in various languages but illiterate. That may be perfectly acceptable given your goals. If you only want to speak freely, you don’t need to focus on reading and writing.

You Need the Right Methodologies in Place to Reach Fluency

A distant second to the content is the methodology you use to learn your content. Why “a distant second?” As a person who has developed dozens of language learning courses and his own language learning methodology, people find it curious that I seem to downplay the importance of methodology.

It’s not that methodology doesn’t matter; it’s just that it depends on the nature and volume of content you’re trying to pick up.

For example, let’s say you want to learn a few dozen phrases and some technical vocabulary. The volume and depth of your content are so straightforward that even the most inefficient methodology will work. Whether you write them out every day, build flashcards, use a spaced repetition system app, or any other method, you’ll eventually pick up the content you want.

If you’re looking to master 2,000 Mandarin characters, however, writing them out every day might not work. The sheer effort of learning the strokes necessary for each character reflects a learning hurdle unto itself.

There are lots of language learning methods that are helpful. Use what works for you. I don’t believe there is “one method to rule them all.” If you’re serious about learning a language, you should try as many different things as you can. You don’t know what works for you until you attempt it, and it’s very unlikely there is only one thing that works for you.

Try everything you can get your hands on, but drop it like a hot potato if it’s not fun, interesting, or delivering results.

The Power of Time and Consistency

I’m going to lump these last two variables together because they’re more connected than you might think. There have been points in my own language learning efforts where I’ve spent upwards of four hours a day, five days a week studying a language. There have been other stretches where all I could afford was 15–20 minutes per day.

I don’t think I’d ever recommended going beyond four hours per day, nor do I think less than 15 minutes per day is enough to make meaningful progress. But that’s because time is just one side of the coin. The other side is consistency.

When I was studying four hours a day, I had very specific goals in place, and I was able to do so for a period of about eight weeks. Once my eight weeks were done, I’d accomplished my goal, and I shifted into a lower-intensity study schedule.

When my youngest child was born, my life changed. I found I was only able to invest about 15–20 minutes per day.

You may have picked up on the fact that I use the words “afford” and “invest.” That’s because time is the absolute most precious commodity you have. You can always earn more money, but you can never earn more time. I am ruthlessly protective of my time, and you should be, too.

When you combine time with consistency, you end up with something that is sustainable – and sustainability is the last critical variable in language learning success. This is a real-world application of the cliché that “slow and steady wins the race.” It may be a cliché, but it’s true.

The Biggest Reason Why You Can’t Learn a New Language

The biggest obstacle for people who want to learn a new language is fear (and we’ll talk more about that in future sections). They believe they can’t, so they never try in the first place. Don’t sell yourself short. There’s a whole world out there speaking thousands of languages for you to explore. Believe me. If I can do it, anyone can do it. And that includes you!