We’ve talked about the four major areas of language learning: reading, writing, speaking, and listening.

But if you want to understand and be understood in a second language, there are three elements you need to grapple with: vocabulary, grammar, and pronunciation. Let’s start with vocabulary.

How Is Vocabulary Learned?

We need to learn vocabulary through comprehensible input, grammatically correct output, meaningful interactions, instruction, and practice and repetition. What’s most important is to work at a level of difficulty that is appropriate for your level of proficiency.

When we think about how to learn another language, we usually envision deliberate learning activities. However, deliberate learning is only one of the five components of a balanced course and should account for no more than one-fifth of the total course time.

How Many Words Do You Need?

Many language learners believe that once they have learned a certain number of words, they can consider themselves fluent.

When I was starting my language-learning journey, I was obsessed with this idea. If only I knew the 500 most common words… the top 2,500 most common words… the top 5,000… I’d be fluent, right? No. Counting words isn’t an effective way to evaluate fluency.

There are several reasons this approach is ineffective:

- It’s impossible to come up with an exact number of words that demonstrates fluency.

- Language experts disagree about how to measure vocabulary size.

- When it comes to learning a language, all words aren’t equal. Some words are more valuable to learn than others, and the order in which we learn words matters.

So, how many words do you need to know to be proficient in a language? Spoiler alert: not only do experts disagree, but they also don’t share consensus on what constitutes a word or on what it means to know a word. Let’s unpack this question.

What Is a Word?

You might assume everyone means the same thing when they talk about a word, but as it turns out, that’s not the case. Language experts sharply disagree about the number of words people have in their vocabularies.

For example, one expert says the average native English-speaking high school graduate knows at least 35,000 words. Another says the average highly educated native English speaker has a vocabulary of 10,000 words.

It doesn’t make sense that people with more education would have smaller vocabularies than people with less education, so where does this discrepancy come from?

It’s the result of experts measuring different things. They don’t agree on the definition of “word” or the definition of “know,” so it’s not surprising they come up with such contrasting answers.

Some experts count every form of a word as a separate word. For example, they count each form of the verb “to see” separately. Using this measurement, “to see,” “see,” “sees,” “seeing,” “saw” and “seen” are considered six different words. These experts apply the same logic to nouns, counting “cat” and “cats” as two separate words.

Other experts count only the root word, not its different forms. As a result, they come up with smaller numbers. These experts count “to see,” “see,” “sees,” “seeing,” “saw” and “seen” as one word, because they’re all forms of “to see.” They also consider “cat” and “cats” as a single word, because the singular and plural words are forms of the same root noun.

Their thinking is that when people learn a root word, such as “to see” or “cat,” they are learning a new word for the first time.

However, when the same people then learn a different form of the root word, such as “seeing” or “cats,” that should be considered an addition to their knowledge of grammar instead of an expansion of their vocabulary.

What Does It Mean to “Know” a Word?

Experts also disagree on when a person knows a word. People who study languages make a distinction between active vocabulary and passive vocabulary.

Some think people “know” a word only if it’s in their active vocabulary, while others believe they “know” all the words in their active and passive vocabularies combined.

A word is in your active vocabulary if you can remember it quickly and use it without hesitation in your thoughts, speech, and writing.

A passive vocabulary word is one you can recognize and understand when you hear it or see it, but you can’t easily remember it and aren’t comfortable using it in conversation.

For both native and non-native speakers, the number of words in their passive vocabularies is usually several times larger than that in their active vocabularies.

People absorb a new word into their passive vocabularies after they see or hear it the first few times. Then, as they encounter the word more often and better understand its context and different meanings, it becomes part of their active vocabulary.

Furthermore: One of the best ways to expand your knowledge of a language is to move words from your passive to your active vocabulary.

Using Vocabulary Ranges Instead of Word Counts

Now that we have seen why language experts generate such different word counts, we can return to our original question about how many words you need to know.

We’ll discuss what it is to be fluent later, but to get a general idea, we’ll measure vocabulary by counting only root words (not their different forms) and the words in your active vocabulary.

A beginner typically knows about 500 words and can use and understand basic phrases when speaking slowly. Elementary skill indicates a vocabulary of about 1,000 words and the ability to understand simple expressions and communicate immediate needs.

An intermediate skill level covers about 2,000 words. You can understand common issues and take part in conversation.

Upper intermediate students know 4,000 words. They can understand complex topics and speak spontaneously. Advanced students know 8,000 words and can easily and spontaneously express ideas.

And finally, mastery of a language reaches 16,000 words and means you can comprehend just about everything you read or hear.

Looking at these ranges, you may say, “I’d like to aim for an elementary skill level before my trip to Spain next year.” Great, you’ve clarified your goal. So how do you choose the most efficient way to learn the vocabulary words you need to achieve it?

How to Study Vocabulary (3 Steps)

Here’s my recommendation.

Step 1: Decide What Kind of Vocabulary You Want to Learn

If you could wave a magic wand and have any learning materials you wanted delivered to you instantly, you would start by deciding what kind of vocabulary you want to learn. This may sound trivial, but it’s more nuanced than you might think.

Questions to consider to narrow down your vocabulary scope:

- Are you flying to Germany for a trade show on industrials? You might want to pick up specialized technical vocabulary to understand the gist of what people are discussing.

- Maybe you work at a hospital with a large Russian-speaking community in Brooklyn, New York. You might be interested in learning some basic anatomy and words that describe major medical issues.

- Or maybe you’re an accountant who works in a large Spanish-speaking community in Los Angeles. Your focus might be on vocabulary that deals with math, numbers, and tax issues.

Of course, these are specialized use cases. More commonly, language learners want to pick up general-use vocabulary, so let’s assume you’re a general-interest language learner.

Step 2: Get a Vocabulary List

There are several kinds of vocabulary lists from which you can choose.

Sight-Word Lists

For example, you might start with something called sight words. These are basic words often targeted at young children. Most of these words are concrete and cover a narrow range of topics. Common sight words include mother, father, dog, cat, tall, short, eat, cry, play, and sleep.

These words are as valuable to an adult language learner as they are to a native-speaking child. Sight-word vocabulary lists range from 50–250 words.

While sight-word lists are common for English, they’re not always easy to find for other languages. You can typically find free word lists with an Internet search.

Travel-Word Lists

Alternatively, you might want to pick up common travel words. These lists can be found in a variety of travel phrasebooks, and they cover a broader range of vocabulary.

There’s a greater emphasis on abstract terms like “justice” or “political system.” Travel-word lists are typically deeper in their scope and might cover uncommon words.

For example, the food section of a travel-word list might include words for lobster, muscles, clam, and tartar sauce.

While I’m sure you know these words in English, you probably wouldn’t use any of them as often as the word “breakfast.” In fact, you could replace most of them with “seafood.”

Travel-word lists can be found in any number of travel phrasebooks, though it’s rare for phrasebooks to provide them all in list form. More often, they’re spread throughout the book, so it can be difficult to extract them.

Word-Frequency Lists

Finally, you can try taking advantage of word-frequency lists. Lists like these are easy to find for widely spoken languages but almost non-existent for languages with fewer native speakers. The reason for this is simple: they are difficult and time-consuming to produce.

English word-frequency lists, for example, are produced every few decades by researchers. They gather a large sample of text in print, video, and audio across a range of subjects, and then data-mine the words and rank them in frequency.

A similar process is followed for other languages, but it requires plenty of content in lots of media and numerous people to data-mine it. That’s why lists like these are less common for languages that are not as popular.

You can purchase word-frequency lists in book form from a variety of publishers, and there are several open-source lists freely available on the web. If you go this route, I suggest using a free list.

Most lists range from 1,000 to 10,000 words, with many languages providing at least 5,000 of the most common words.

The reason I suggest going with a free list is simple: if you’re an academic statistician, you may need to know whether the word for “mom” is more frequently used than “dad” or whether the formal “mother” is more or less common than the casual “mom.”

But if you’re a language learner, none of this matters to you, so long as these words are on your list. Additionally, those words are so commonly used, I can virtually guarantee they will be on any list you select.

Having said that, I’ll tell you that the list I want doesn’t exist. I’ve always been surprised at the lack of effort to develop a helpful-word list.

I’ll give you an example. In every English word-frequency list I’ve ever seen, “the” is at the top of the list. The next entry is “a,” which trades the top spot with “the,” depending on the list.

While “a” and “the” are frequently used words, they’re not especially helpful.

You could learn everything in the English language other than definite and indefinite articles and still be understood by native speakers. (If you’ve ever spoken to native speakers of Slavic languages like Russian, which lack articles, you know what I mean.)

Think of a classic spy movie: “I detonate bomb now, Mr. Bond!” Does the lack of “the” before “bomb” confuse Mr. Bond? Clearly not. But I digress. Let’s get back to how to learn your vocabulary.

Step 3: Begin to Study (with Some Caveats)

Once you’ve selected your word list, it’s time to dig in — with some caveats.

Variety is the spice of life.

Make sure your word list covers a range of parts of speech, including nouns, pronouns, adjectives, verbs, and adverbs. This is important for building basic sentences as you expand your vocabulary.

If you only tried to memorize the parts of the body, how would you tell someone that a part of the body was in pain? If you focused exclusively on foods, how would you tell someone you were hungry, or that a particular food was tasty or bland?

Similarity can be spicy, too.

While you’re at it, figure out whether the language you’re learning has any cognates in common with English. What are cognates? These are words common between two languages. Sometimes they are spelled the same; other times, they are pronounced the same.

However, it’s rare that they are both spelled and pronounced the same. Words like “Internet,” “coffee,” and “metro” are cognates commonly shared between many modern languages.

At the same time, be wary of “false friends.” These are words spelled or pronounced similarly between languages but with very different meanings.

For example:

- Spanish: actual → “current” in English

- French: bras → “arm” in English

- Italian: morbido → “soft” in English

- German: winken → “to wave” in English

Method Counts When Learning Vocabulary

You might be tempted to study vocabulary by reading words out loud, writing them down, labeling things in your home with Post-it Notes, or building flashcard decks, either in real life or with apps.

None of these are bad approaches, but do you remember the difference between learning and studying?

Both are important, but studying isn’t the same as learning. Anyone who has ever studied for a test only to fail the final exam knows this all too well.

So while you can and probably should try some of these methods, you should also attempt to learn your vocabulary by learning the words in context. This requires the use of common phrases and basic sentences.

How to Learn Words in Context

Learning words in phrases and sentences is one of the most widely used methods successful language learners use to build large vocabularies quickly.

Variations of this approach are sometimes referred to as “mass input.” This is a real-world application of the Input Hypothesis developed by Stephen Krashen, which I covered earlier.

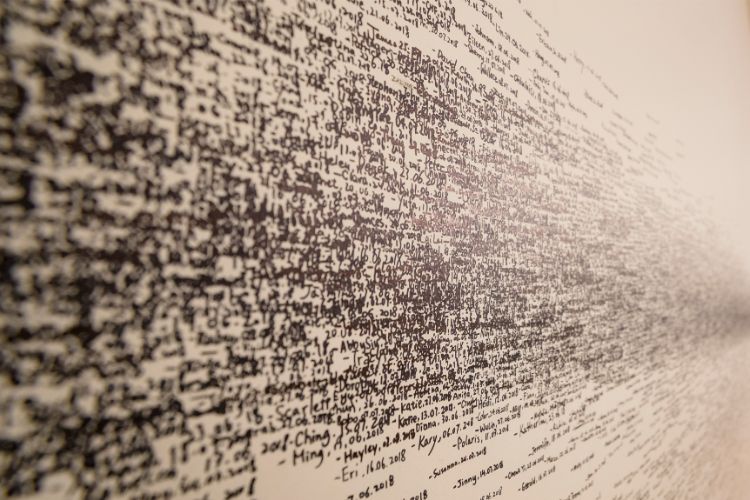

Another real-world application of this approach is called “sentence mining,” or the “10,000-sentence approach.” Adherents to this method expose themselves to 10,000 sentences translated between English and their target language.

There’s no active attempt to memorize, just to comprehend. The idea is that with a large enough sample of sentences, the language learner will naturally develop a significant vocabulary and an intuitive sense of the grammar of a language.

Don’t Focus on Memorizing Definitions

Many people begin their language studies by attempting to memorize high-frequency words and their definitions. Adherents often focus on the first 500–1,000 most frequently-used vocabulary words in their target language.

There’s nothing wrong with that; I’ve used this approach with several of the languages I’ve taught myself.

But if this is an approach you’re considering, give careful thought to where you get your vocabulary lists and how they were created. Go back to our exploration of “what is a word” and consider how you choose to study definitions.

You don’t need to memorize every definition of the words you are learning. That would be very time-consuming because some common words have several alternative definitions.

For example, in English, the word “murder” normally means “to kill.” An alternative definition is “a flock of crows.” This secondary definition isn’t commonly known among native speakers, let alone language learning students.

It’s far more efficient to learn only a few of the most common definitions — the ones you’re likely to need in ordinary conversations. Then, with experience, you’ll naturally learn more when you hear the words used in different contexts.

Through exposure over time, you’ll assimilate the language.

Learning Vocabulary in a Natural Way

There’s no precise number of words you need to know to become fluent in a new language. In part, that’s because language scholars use different measurements to count words and have different standards for what it means to know a word.

It’s more useful to group people by their language proficiency according to a rough estimate of the number of words they know, such as the CEFR ranges.

In my opinion, learners who know:

- 250 to 500 words are beginners

- 1,000 to 3,000 words can carry on everyday conversations

- 4,000 to 10,000 words are advanced language users

- 10,000+ words are fluent or at a native speaker level

When it comes to learning a language, all words are not equal. Learning some types of words will accelerate your progress more quickly than other types of words.

To efficiently learn a language, focus on the most common words before studying more specialized vocabularies and learn the most common definitions first.

You’ll progress fastest if you start by learning what you can use right away.

If, instead, you try to read a dictionary from cover to cover, grasping every word and definition in the language, much of your effort will be inefficient at best and wasted at worst. (I know because I tried — and failed — using this method.)

Learning the most common words and definitions puts you in a position to assimilate the language in a natural way. The more you hear and read words in the language, the more you will understand new words and meanings from their context.

This is similar to the way you learned your first language as a child. The more you expose yourself to your new language, the more fluent you’ll become.

Take a Broad Approach… and Have Fun

I’ve mentioned before that your language-learning efforts should be relevant, engaging, fun, and within the context of what you want to learn. I’ve seen many (struggling) language learners focus almost exclusively on the study of a language.

They sometimes spend hours per day slogging through textbooks, unable to move on to the next chapter until they have memorized 90 percent of the material.

This isn’t an effective approach. It’s not enjoyable, which means you’ll eventually burn out, and it’s unnatural. It’s OK to use a textbook. I’d argue it might be better to read short stories. It’s fine to play video games, listen to the radio, work with a tutor, or watch YouTube videos.

Just remember that you’ll be far more successful if you expose yourself to a broad range of inputs and enjoy them than if you focus intensely on memorizing a narrow range of content.